16 December 2014 - 10 January 2015

Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina

Ješa Denegri

PAINTING AS AN ACT OF DESIRE FOR FREEDOM WITHIN THE LIMITS OF THE POSSIBLE

After the recently published monograph on Đorđe Ivačković and its launching in Belgrade, as well as his last solo exhibition in the Gallery RIMA in Kragujevac, what is forthcoming are the endeavours to incorporate this artist and his work – mostly produced in Paris but well-known and appreciated in the Serbian and former Yugoslav artistic circles – into the contemporary local cultural heritage hoping that the condensed retrospective of Ivačković in the Museum of Contemporary Art of Vojvodina in Novi Sad will make an important contribution to those endeavours.

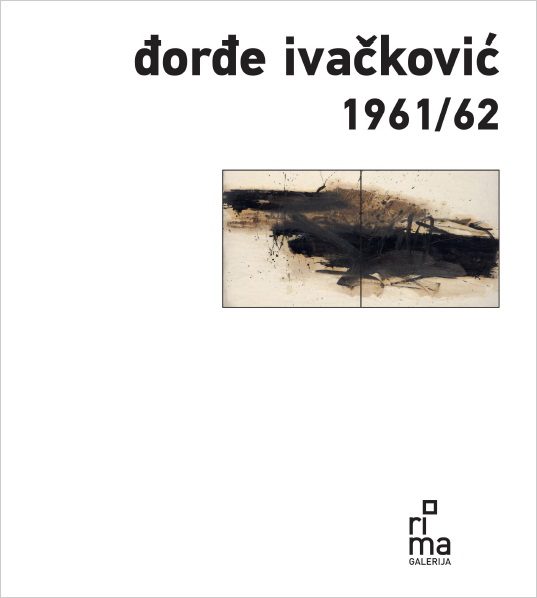

Ivačković’s case is a completely isolated example among the many Serbian artists of several generations who worked in Paris after the Second World War. After having graduated from the Faculty of Architecture in Belgrade, he went to Paris in 1961 where he began his painting career. He relatively soon had his first noticeable appearances in that big art centre, from his first solo show in 1963 to his participation in the selection of the host country at the Biennial of the Young in 1965.

But his first leanings to painting and the decision to practice painting rather than architecture, Ivačković had made already during his studies in Belgrade. When remembering his beginnings in art he spoke of the influence several exhibitions had on is final decision, exhibitions such as Contemporary French Painting (1952) and even more crucially Contemporary American Art from the Collections of the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1956) where he got acquainted with the works of the pioneers of lyrical abstraction and abstract expressionism. He later supplemented the knowledge acquired then during his visits to the exhibitions of contemporary abstract art in Italy and Germany. It is particularly indicative of Ivačković’s painterly formation that he had chosen his paragons and developed his affinities first mentally and intellectually and then only gradually learned the obligatory technical procedures of painting by practicing exercises in style according to the previously chosen models. The French and American schools were my paragons and guides, the councillors of my awareness of what is painting, he said in a conversation with Lidija Merenik, published in the magazine Moment (No. 16, 1989). An equally important role in the character of his painterly determination had his youth passion for contemporary music, more precisely jazz: Ivačković was one of the first devotees to jazz in post-war Belgrade (as conscientiously studied by Nevena Martinović in her text Đorđe Ivačković: painting and jazz, published in the catalogue of his exhibition in the Gallery RIMA, 2014). So, he came to Paris, fully prepared and determined regarding the sphere of his interests: and one of the first exhibitions he took part in was 30 peintres inspirés par le jazz (1965) organised by Jean-Jaques Lévèque, art critic, who would later be a crucial support to Ivačković in his early appearances and who that same year proposed him in his author selection as one of the participants in the Biennial of the Young.

His participation in the Biennial of the Young in 1965, when he displayed big format abstract paintings (260 x 240 cm) prominently mounted in the entry hall of the exhibition space, had long-lasting consequences on Ivačković’s future career. On the one hand, it opened the possibilities for him to enter the gallery world of Paris, from his solo show in the Gallery Cimaise Bonaparte (later known as the Gallery Daniel Templon) in 1963, and on the other, he was noticed then by certain art circles and personalities from the country of his origin and would later be invited to exhib in Belgrade and take part in the Triennial of Visual Arts in 1967 and 1970, as well as the October Salon in 1969 and 1970, to his first solo exhibition in the Gallery of the Youth Club in Belgrade in 1971. From the mid-seventies Ivačković had regular exhibition contacts with the Gallery Nana Stern where he had five exhibitions (1975, 1977, 1978, 1980, 1982). In that period he had two solo shows in Belgrade (in the Salon of the Museum of Contemporary Art (1977) and in the Cultural Centre Gallery (1981).

In his preface to the catalogue for Ivačković’s exhibition in the Youth Club Gallery in 1971, the French art critic Georges Boudaille indicated possible adequate reading and interpretation of the characteristic typological features of his painting. Boudaille believed that Ivačković’s painting belonged – as art critics usually say – to the great stream of lyrical abstraction… At the same time he introduced in this explicit statement a crucial correction: lyrical abstraction was not a definitely finished artistic phenomenon of the 1950s, lyrical abstraction was still evolving in many different aspects and continuously inspired the production of unknown forms. The following conclusion proceeds from such insights and can be referred to Ivačković’s painting: starting from experiences of the pioneers, lyrical abstraction evolved and continued – from the mid-sixties onwards – in new and current expressive potentials and therefore Ivačkovič’s painting should never be identified with the historically verified term such as lyrical abstraction but should, on the contrary, be considered in the light of the just mentioned evolution and continuation, in categories that assumed and required different denominations for the essential characteristics of his painting.

The key factor of the linguistic difference between historic lyrical abstraction and abstract painting later, to which Ivačković’s art can be added, follows from the entire epochal cultural context. While the historic lyrical abstraction had a post-war philosophical pendant in existentialism, abstract painting of the sixties and seventies had its pendants in structuralism and post-structuralism, as doctrines that directly or indirectly influenced the theoretic and critical interpretation built into the basic critical readings and interpretation of the then contemporary artistic practices, and also the then current versions of abstract painting such as the variation Bernard Lamarche-Vadel denoted by the term analytical abstraction. According to him:

Analytical abstraction should be separated from a number of general streams called abstraction… If lyrical abstraction in this respect treats the painting itself, the base on which the praxis of the painter is realised, that praxis will be filled with some other content which is not the content of the painting but an emotional discourse of behaviour, emotional expression of the painter, a things which is not the real discourse of the painting but belongs to the psychology of the painter. It was necessary to remove from the painting its exterritoriality, its declarative quality, because the problem is contained in the need to prove that a painting is not literature and that any kind of literary insertion into a painting leads to a loss in the structure of the painting… In other words, let us define roughly and rapidly the analytical abstraction: it is an attempt to bring back the pure construction of a painting, the reduction of everything that can represent a return to the internal elements which do not belong to the praxis of the surface and the base of a painting…

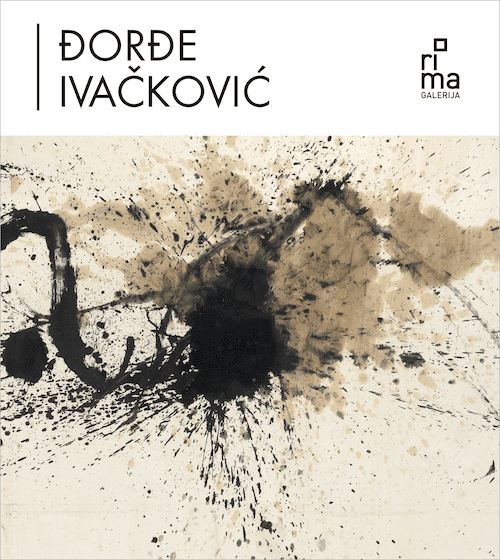

It can be perceived that Ivačković’s painting, and particularly in the early Paris period when the share of improvisation during the process of execution is exceptionally emphasised (influenced by the artist’s strong fascination with jazz), departs to a great degree from the strict analytical procedures of elementary or primary painting, but even then it consistently follows the principles of total unreferrentiality, as confirmed by the following statement of the artist:

I have chosen the purest visual language without any direct connection to associations… The most important characteristic of my painting is the organisation of these essential elements in relation to the given surface leading to a certain reflection – to the visual meaning of the painting… The art of painting has obtained its complete autonomy and become an absolute artistic category, just like music.

In his statements about his own painting Ivačković insists on the coordination of two fundamental operational factors denoted by the concepts of adventure and programme:

I believe that adventure is an important element of realisation: I want to be aware of my mistakes, hesitations, repentances, of all the elements that make up our everyday life. With regard to my composition, I have a general notion – for example, I know that I want to make a vertical. The composition is then linked and later harmonised with a series of actions which are, it seems to me, programmed.

And on another occasion:

That process is perhaps pre-programmed in my mind… With me, it is a kind of pre-programmed automatism. The materialisation of inner happenings. The realisation itself is impulsive, but it is not unconscious.

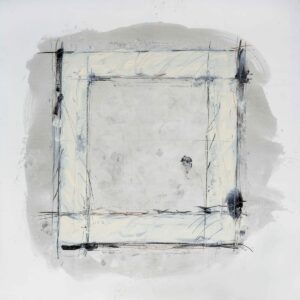

In these quoted statements (and other remarks about his own works) Ivačković is clearly auto-reflexive and aware that he performs the practice of painting according to a series of preconditions, even rules he conscientiously follows. Such as: the square format of the painted field (the canvas or paper) as the base of the painterly operation; that base is always white, like a sheet of paper, and the act of painting/writing is performed on it, always one, unique, performed in one séance and therefore cannot be supplemented or corrected after it has been terminated and definitely completed. The act of painting is most frequently performed on several paintings simultaneously, on canvases or papers placed on the floor, accompanied with the sound of jazz, lasting as long as the artist’s psychological tension and physical freshness, before he is suppressed by saturation and fatigue, in other words, while the joy of painting and pleasure with painting is alive within him. A painting executed in the described way does not hide any other or additional meaning: the painting means what it shows, what can be seen in it. The repertoire of painterly moves is founded on the primary elements of the medium of painting: stroke, blot, dot, all of them separate and together within the painted field. And, the specificity of Ivačković’s procedure in comparison to fundamental painting is in the following: the act of painting, inasmuch pre-programmed (according to the artist) is simultaneously spontaneous, impulsive, improvised, certainly due to his devotion to the music of jazz for which he is permanently trying to find an adequate language in the medium of painting. The concluding valuation regarding the typology of this painting could be the following: it is a treatise on the nature of painting contained in the very act of painting and the issue of that approach is a picture, simple and resplendent at the same time, mental and visual, particularly obvious in the phase of Ivačković’s painting which Nevena Martinović analysed in the chapter on “The Age of Conceptual Paintings 1972-1981“ and for which the artist would say in his interview with Lidija Merenik:

It was my almost dematerialised period, a square on a square, almost minimal painting with a few free strokes. I used to call that „conceptual paintings“ because, almost unconsciously, I adjusted to the spirit and concept of the time. In those paintings the material, physical aspect is reduced to its own idea, and the language and passions are reduced to a minimum… If you are frank, you cannot do anything else but what your time, the spirit and the mind of that epoch is telling you.

The artistic epoch when Ivačković was active, together with many others, is the period of major turbulences when contemporary art stands between the survival of the classic disciplines such as painting, on the one hand, and an enormous expansion of new technical media and their applications in art, on the other. The issue of the so called „crisis of painting“ has been frequently considered and this has consequences on the work of galleries and museums and the art market as well, particularly perceptible in a powerful cultural centre like Paris. When he wrote about the political foundation and the artistic situation of the French capital city from the sixties onwards, the art critic Jean-Marc Poinsot states the following:

Torn between the search for the specific features of their praxis and the wish to get involved in the community life, artists oscillate between non-art or practice, appropriating non-artistic technologies, and a speculative art faithful to its traditional means.

Ivačković’s painting was on the current art scene of Paris right in the area of a speculative art faithful to its traditional means. It was the area of a new type of abstract painting that did not grow only on the tradition of the European historic abstraction but on the understanding and appropriation of the contributions of American post-war painting, from abstract expressionism and post-painterly abstraction, and the theories of late modernism founded on them, first of all the theories of Clement Greenberg published in the magazines Art Press and Macula, or the collection of texts Peinture américaine, with the introduction by Catherine Millet. The Paris protagonists of the new abstract painting were Martin Barré, Simon Hantai, Olivier Debré, members of the group Support/Surface, all of them Ivačković’s contemporaries regardless of significant differences in the appearance of their painterly morphologies and their theoretic origins. The place of Ivačković’s painting should be looked for somewhere in that orbit, as propounded by the French art critics who liked his art, such as Paule Gautier, Pierre Cabanne and Jean-Luc Chalumeau (who included Ivačković’s art in his book Lectures de l’art, Paris 1981, the chapter Les avatars de l’abstraction) together with Barré, Jean Degottex and François Rouan. In his text for Ivačković’s solo show in the Gallery Studio Kostel in Paris (1990), calling upon Michel Ragon and Marcelin Pleynet, Chalumeau linked him with Antoni Tàpies and François Arnal, explaining his painting as integrally abstract and the only among the so called present day neo-geometric artists who practiced pure abstaction.

Since he had been included in the Serbian and the then Yugoslav artistic scene after his participation in the Biennial of the Young in Paris in 1965, Ivačković took part in many group exhibitions and a few solo ones and was quickly and very favourably received. Lazar Trifunović invited him for his exhibition Abstract Painting in Serbia 1951-1971 in Belgrade in 1971. He was also at the exhibitions of Serbian art organised by the Museum of Contemporary Art in Ljubljana (1971) and Skopje (1972), then one of the selected artists for the exhibition of contemporary Yugoslav art in Brno and Prague (1972), Budapest (1972), and Leverkusen (1977). His works were also included in the important travelling exhibition Tendencies in Yugoslav Art of Today: Tendenzen in der Jugoslawische Kunst von Heute in Dortmund, Berlin, Nuremberg (1978-79), Tendences de l’art actuel en Yougoslavie in Brussels, Luxemburg (1979) and Tendenze dell’arte jugoslava d’oggi, in Rome, Genoa (1979). His contribution to these representative shows was in the supreme quality and emancipated language of his works. He was not so lucky with interpretations of a few local critics who mostly linked him to the historic lyrical abstraction and one of them even thought that with its language, plastic contents and artistic reality his painting belonged to the past. Ivačković’s painting will have adequate readings in the early eighties and one of those was written by Tonko Maroević who separated him on the occasion of his solo exhibition in Zagreb in 1981 from any kind of revival, abstract expressionism or informel art and, on the contrary, recognised in his art several analytical suggestions. As time went by and Ivačković painted and exhibited less frequently in Paris it became more obvious that his permanent place in the historic memory was in the context of the Serbian art from the second half of the twentieth century, particularly confirmed by the fact that, apart from the memorial exhibition in the Serbian Cultural Centre in Paris in 2012, his last solo exhibitions were organised in Belgrade (2009) and Kragujevac (2011 and 2014).

I adore painting…for me it is an eternal adventure in front of a new and unknown situation – with these words Ivačković finished his already mentioned interview published in the magazine Moment. However, it seems that it was much more than a fascinating adventure for his painting and his vocation of a painter. When he dreamed of becoming a painter during his studies of architecture it was certainly because he sensed that only painting as his chosen vocation would provide for him the promising feeling of freedom that he could not find in the profession he was educated for. And also, that painting could secure that feeling for him primarily if he went to Paris as a young man and that there, regardless of his origins, he could fight for a free self-assertion according to his own abilities and where he could learn much about painting if he knew how. Ivačković entered the world of painting at the moment when early abstraction practiced by the great pioneers and lyrical abstraction of post-war protagonists already belonged to the closer or farther historic past, and because of that his generation was bound to learn well the language of painting and apply it with full awareness of the specific features of this ancient but still vital artistic discipline. Ivačković proved to be ready and able to build on the foundation of this awareness his own understanding of a new aspect of abstract painting, coherent in the application of pure abstraction, and still rich and diverse in the phases he went through, from a direct inspiration by the music of jazz to those that he and art critics as well would call the age of conceptual paintings and the period of energy structures. When observed as a whole his opus today does not only reveal painterly qualities but stands as a realisation of an innate human aspiration to freedom within the limits of the possible, as he himself condensed in the following convincing statement:

I make variations on one theme: the rectangle in the square, a square within a square and the freedom all these possibilities offer. Of course, the space for action is limited. I believe it matches the picture of life: we develop within the restraints and structures where we are looking for freedom. My freedom is the way to express myself on the canvas after I have accepted the restraint. The man imposes those restraints upon himself to test his possible freedom. In the end, art is the picture of our position.