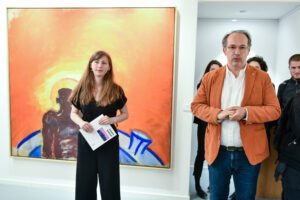

Marija Stanković

The nature of/and the bodies in the painting of Kosara Bokšan: the cycles Icarus and Woman-mountain

Kosara Bokšan appeared in the world of art as a strong ethical and unwavering artistic personality. The maturing of her visual expression was a process permanently interwoven in the net of social, political and cultural developments after the Second World War and during the second half of the twentieth century, accompanied by a passionate search for freedom. Her exhibitions in the cities of the (former) Yugoslav artistic space, her participation in the famous artistic manifestations in Paris and solo shows in Lille, Paris, Strasbourg and Rome, marked her active presence as artist and also her place in the Serbian, Yugoslav and European history of art.

She liked to draw even when she was a little girl, but, as she used to say, a serious and true work began first at evening life drawing classes in the school of Mladen Josić at the Kolarac People’s University, and then afterwards in the studio of Zora Petrović in 1944. As a student of painting at the Academy of Fine Arts she was in the class of Ivan Tabaković, who used to systematically awaken curiosity in his students in order to open new vistas for them. The presence and influence of such a powerful artistic personality as Professor Tabaković was of great importance for the students who were maturing at the Academy at the time of ideologically hard-core Yugoslav post-war art. The monolithic political and social structure ruled over the artistic world and required from art to present only the newly developing revolutionary society. In 1947, seven students from the Academy, Kosa Bokšan among them, stood against the standards of the ruling communist doctrine and decided to go to Zadar, away from the demands of the institutions. The communards of Zadaror the Zadar group was formed then comprising brave, young, artistic personalities who, although not acting with political awareness, had made a significant step forward in the overall Yugoslav artistic situation just by not wanting to participate in it. Each of them in his or her own way, as youngsters but not beginners, as Lazar Trifunović used to say, they were heirs to the inter-war painterly legacy and thus sustained the well-known artistic ideal.

The time spent in Zadar, described as a vital and artistic rebellion, was of particular importance for the formative period of all members of the group, including Kosa Bokšan. It lasted until 1952, to the moment when Kosa Bošan went to Paris with her husband, the painter Petar Omčikus. The landscapes, portraits and self-portraits from her formative period (1946-1951) were produced in the spirit of expressive realism, and although thematically representative, they comprised evident predispositions for abstraction. After the arrival in Paris, where abstract painting was exceptionally present on the artistic scene both in its geometric and lyrical form, Kosa Bokšan was able to realise the aforementioned inclination. Figuration was removed from her expression and abstract, initially slightly geometricized and flat, compositions that would later become lyrical and pastose, inhabited her canvases until 1960. The abstract fascination, as the artist used to say, was in fact an episode in the maturing of (her) painterly considerations. The legacy of abstraction was then incorporated into the experience of Kosa Bokšan and it has been important for the understanding of the genesis of visual processes in her future output.

The Real Places and Symbolic Spaces

(…) even in my childhood, although we lived in Belgrade, we had a big garden in our family house, with a high walnut tree, with land, so that I have always been in contact with nature.

The main relationship built and developed in the painting of Kosa Bokšan was dedication to nature as a place to be in and create, as the origin of inspiration and an element that generated the thematic, compositional and spatial orientation of the picture. The need to be in nature was always accompanied by the need to intervene artistically and transform the seen into creative visual spaces. The origins of such dedication to nature can be found in artist’s childhood. When she talked about growing up in a scholarly atmosphere, owing to her father, an engineer, she also underlined that her mother alleviated that sternness with her warmth and her philosophy of return to nature. In that sense the importance of nature in the life of Kosa Bokšan can be first observed as a family legacy empirically proven throughout the main phases of her life and artistic activity.

The formative period of her art was marked by the life in Zadar, so that the need to create freely in a natural environment was a process that defined nature as an important place for contemplating art. After Zadar, Kosa Bokšan went with her husband Petar Omčikus along the Adriatic coast, from Rijeka to Bar and Ulcinj. All those places of nature emerged on canvas in a changed form, as a subject matter in the painting of Kosa Bokšan, first as landscapes: the Environs of Rijeka, Old Bar and Ulcinj (1950). The effect of her countryside pictures, painted with expressive strokes, pastose layers of paint in impressive colours, led to a visible obliteration of recognisable forms by the swings of her creative charge. Perhaps they were the best indicators of the aforementioned potential of an abstract painterly poetics, still within the borderline of objectness owing to a moderate visual recognition of the motifs and clear geographic references in the titles. After her abstract experience in Paris, purified and completed, in 1961, while she was on the bank of the Danube in Ritopek, Kosa Bokšan created a series of works inspired by nature, which changed the previous abstract nature of her art, but abstract relations of her painterly considerations became integral parts of those works: Ritopek and three versions of Maize (1961) The art historian Ješa Denegri found a parallel to this phenomenon in the famous expression of the French theorist Michel Ragon – abstract landscape, who also noted that such painting addressed nature without describing it.

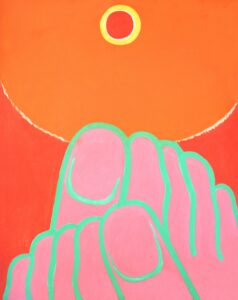

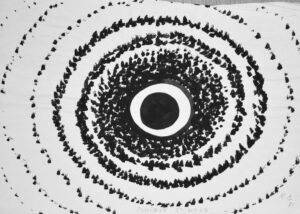

Apart from Zadar, the Adriatic coast and Ritopek, important places on Kosa Bokšan’s map of nature also include the south of France, where she stayed in 1965. In that period, the artist was inspired by the study of light problems and of the bathers whose bodies/bodily fragments she sketched in her drawings. The studious approach of her drawings was interpreted as a direct and free dialogue with nature and the world. The analytical processes of sketching, deconstruction and transformation of the seen determined the space within which the perceived was reconstructed in order to become a symbolic form that frequently had its analogy in the painting. The study of the problem of light was realised in a series of works produced in 1965 (The Sun, Sun on Dark Background, Phases of the Sun II) with sun in their focus as the central motif and element the picture was structured around. The sketched bodies of bathers remained an idea registered in the drawing, to be revived several years later in her paintings Composition – Drunken Boat, Bathers and Odysseus (1967), when she was in Vela Luka on the island of Korčula. Kosa Bokšan and her husband Petar Omčikus had a studio built there. As a contemplative and working space, the studio was (yet another) invigorating place for painterly speculation and work in nature and with nature.

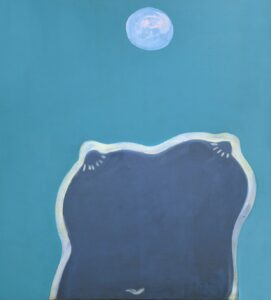

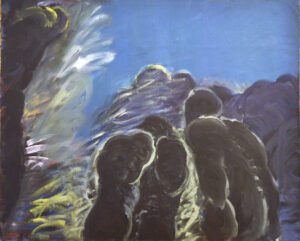

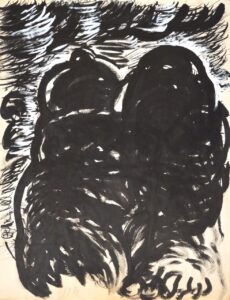

In those years, the perceived countryside was transformed into mental landscapes that became symbolic pictorial spaces owing to the activity of the artist. Composition – Drunken Boat was an iconic representation of that period, significant primarily as homage to the painter Sava Šumanović, it was also a refreshed memory of the sketched bathers from the south of France and their relationship to the bathers in Vela Luka, as initiators of these reminiscences. In the fore front of the painting there is a blue boat and the observer is confused because it is not possible to distinguish the boat from the sea. There are bathers in the boat but their bodies seem to dissolve, almost distorted under the heat of the sun. A particularly important segment in the lower right corner is an unobtrusive and unidentified form of female back. As previously sketched, it appeared in her paintings Little Zenith and Zenith (1968). The curvy, “seductive” form of the female back, although recorded as a reaction to the visual fact of a corporeal female body, in this case became a symbolic surface of the bodily that removes the nakedness from itself and dresses in art. The idea, embedded in this picture would be transformed in 1975 into her Medusa Raft, when another kind of bodily texture was actualised.

(Complete text in printed edition)