10 November - 31 December 2018

Sofija Milenković

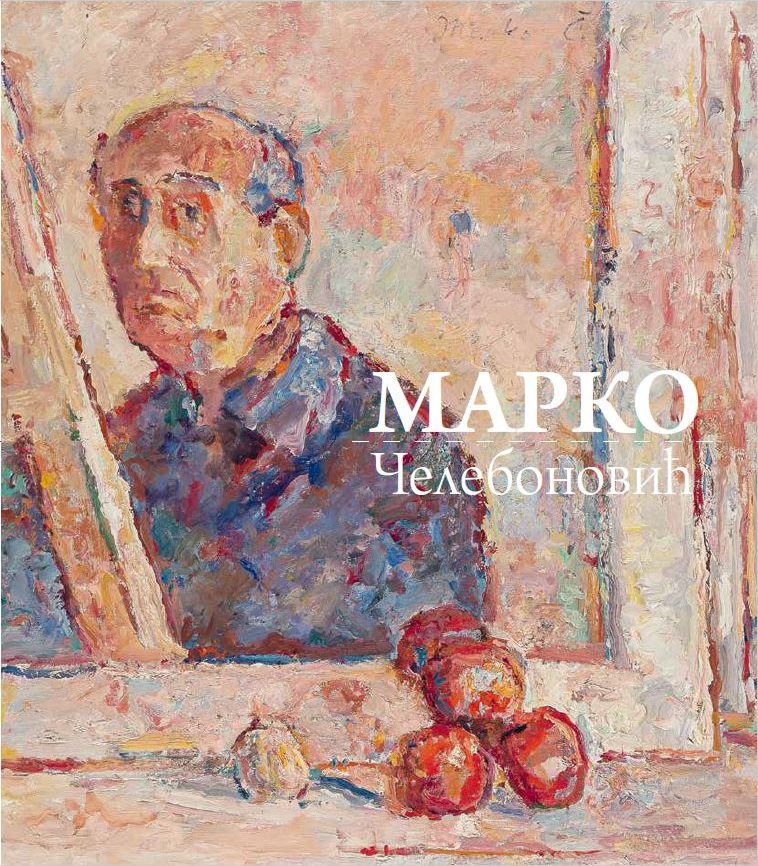

The Early Opus of Marko Čelebonović

In making a recapitulation of his overall artistic activity in 1981, Marko Čelebonović offered an important conclusion in a conversation with his brother Aleksa: “With me, one period never stopped abruptly in order for another one to begin. They has always been a natural continuation even without my will, although I am aware of differences between them”. Nevertheless, for decades, the historiography dedicated to his output did not treat his works as a continuous whole, but as successive chronological phases, established on the basis of a formal-linguistic analysis of the works and according to the model of progressive and straightforward movement of art. Such a periodisation of Čelebonović’s opus not only restrained any systematisation that honoured the organic structure and equal analysis of the most important conceptual elements, but its consequence was also a systematic isolation or neglect of certain segments of the opus that would not fit easily into the set logic of development or were considered marginal for its understanding. Such is the case with Čelebonović’s earliest corpus of works, produced in the 1920.

In that earliest period, Čelebonović created a stylistically and conceptually diverse opus that could crudely be divided into two groups according to the contexts of its production: to the subgroup from Paris and the subgroup from Saint Tropez, subsequently differentiated on the basis of formal, thematic and philosophical elements. While the first subgroup has been considered separate from the rest of Čelebonović’s opus as an atypical beginner’s experiment because of its morphological and thematic differences, and as such was considered unimportant for the understanding of Čelebonović’s later or overall praxis, the other subgroup, created towards the end of the twenties, was automatically attached to the corpus of works from the thirties because of its morphological and thematic similarities that define the essential aesthetic and theoretic stipulations of Čelebonović’s entire output, and was considered his introductory phase, the beginning or transitory period. Čelebonović’s works from the twenties have never been observed as an integral whole within which one could follow the dynamic changes that show the way in which Čelebonović established, changed or preserved the problematic foci and principles of his artistic approach in very different contexts. The moment and the mode in which the professional public got to know Čelebonović’s first works, and the absence of relevant data, documentation and evidence about this period of his activity, have also largely determined the problematic relationship towards the whole produced at the very beginning of his artistic practice that lasted for over sixty years.

Contrary to other artists of his generation, with whom he was later associated in the surveys of Serbian modern art, Čelebonović did not begin his artistic praxis in Serbian or Yugoslav environment and moved later to Paris. While he was establishing indirect connections with Yugoslav and Belgrade art scene in the twenties and the most part of the thirties by means of his acquaintance with Yugoslav artists who stayed in Paris or his participation in groups of artists and regular presence at Belgrade and Yugoslav group exhibitions, the first opportunity Yugoslav cultural public had to get better acquainted with Čelebonović’s opus, created primarily in the French context during the interwar period, was his first solo show in Belgrade, in 1937, at the Art Pavilion Cvijeta Zuzorić. The focus of this exhibition were his works produced in the 1930s, just as in the case of his first post-war solo show in Belgrade in 1952, which, as we know, chronologically began with the works from the late twenties. Because of all this it has been believed that thirties marked the beginning of Čelebonović’s artistic and exhibition praxis and the works from the late twenties were its introduction. With the earliest works from the twenties, created in Paris between 1923 and 1926/1927, the real beginnings of his artistic activity, the professional public got acquainted only in 1966, when they were presented at the retrospective exhibition in the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade. As stylistically and thematically completely disparate from the rest of the output by which Čelebonović became known, this whole was added to the existing corpus and was never truly considered as constitutional elements of his artistic development.

The stumbling block standing at the beginning of any revision of an early artistic activity is the chronology that causes suspicions regarding interrelations and the time of origin of different subgroups of Čelebonović’s works from the twenties. The first analysis and periodisation of the earliest cycle was prepared by Miodrag B. Protić in the catalogue of the mentioned retrospective from 1966. On that occasion, the works with mostly unknown years of origin and with the style and subject matter undoubtedly different from the later ones, had to be dated, categorised and analysed. In absence of reliable bench marks and documentary material that could facilitate the untangling of chronology, Protić used the dating offered by works themselves. The following works were exhibited from the early opus: Nude from the Back, In Front of the Circus (the artist dated them in 1925), The Bird Seller, Billiards (the artist dated them in 1927), then Chicken Coop and Woman with Parasol, In Front of the Tavern (all three the artist dated in 1928), Group and Woman with a Straw Hat. Protić then determined the beginning of the artist’s painterly activity sometime in 1923 or 1924, while today we know that the first paintings were undoubtedly made in 1923: “It was over with sculpture: we were already in 1923”, said the artist. Judging by the signature, the painting Two Figures, subsequently dated in 1923, was one of the first Čelebonović’s works; together with it there are paintings with similar characteristics and subject matter, Hair-combing, Nude from the Back, Bucolics and Woman in Green with Pitcher on Her Shoulder. However, the main dilemmas regard the paintings in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art, which are dated in 1927 – Grape-picking, Billiards, Interior – Woman in Front of the Mirror and The Bird Seller. Their formal and thematic characteristics, as well as a certain number of biographical data, indicate that those paintings could have been produced earlier, particularly when one takes into account that paintings such as Vreni and Flowers, Woman and Child, Miss Claude, Annette Lecoq, distinctly dissimilar from the previous group, were dated in the same liminal year – 1927. Protić clearly had reasons to date the paintings from the Museum of Contemporary Art in 1927. Pictures like Grape-picking, Interior – Woman in Front of the Mirror and Bird Seller match in their formal characteristics, style and subject matter, the picture Billiards, and it was logical to accept the artist’s dating without further verification. Since the first paintings from the next group Protić had at his disposal were dated in 1928 – Chicken Coop, Woman with Parasol, In Front of the Tavern, etc. – the chronology he then established seemed to be quite convincing and he defined the interval between 1927 and 1928 as transitional period. All the authors who were subsequently engaged in this period accepted Protić’s dating despite the obvious inaccuracies that emerge with addition of the repertoire of works from the twenties. Lidija Merenik was the first to indicate those dilemmas, more than fifty years since the establishment of such periodisation – and she placed in the centre of the problem the question whether the years of origin of the debatable first group should be moved to an earlier date or others to a later one.

Three happenings seem to be especially important for the solving of this problem. Čelebonović exhibited for the first time in 1925 at the Salon des Tuileries where he sent three paintings: Bucolics (Bucoliques), Woman in Green with a Pitcher on Her Shoulder (Nativité) and Shepherdess (Bergére). Two of those pictures are known to us: Bucolics has not been preserved but it was reproduced in a special issue of the magazine Le Crapouillot dedicated to the Salon des Tuileries, while the picture Woman in Green with a Pitcher on Her Shoulder was bought by the Japanese sculptor Takashi Shimizu and it is still in the collection of his family. On the basis of the preserved examples it can be concluded that until the Salon des Tuileries in 1925 the dominant visual and conceptual model in Čelebonović’s practice was the one found in the painting Two Figures (1923). The very next year Čelebonović had his first solo show in the Galerie Campagne Première in Paris, situated on the corner of the street with the same name and Boulevard Montparnasse. No information or documentation regarding this exhibition has been preserved, except for the official invitation. According to Aleksa Čelebonović, Marko’s working method had already been directed towards the research characteristic of the works In Front of the Circus, Grape-picking, Interior – Woman in Front of the Mirror, The Bird Seller and Billiards, and this could indicate that the paintings could have been produced before April 1926, when the exhibition was held. In that year, after the show, Čelebonović went to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to do his military service, and in the beginning of 1927 he returned to Saint Tropez where he settled with his family. “At that moment”, said Aleksa Čelebonović, “ since he had not painted for several months, a crucial change in his working method occurred: he began to paint after nature”. A similar course of events, with different and confusing versions of the biographical myth about “the first painting after nature” can be found with some other researchers and also in the artist’s own evidence – the common suggestion refers that the change in his orientation happened after his military service and the return to Saint Tropez, or, after the discontinuity of his professional activity and change of context in which Čelebonović had previously worked. This assumption seems logical because in between the two groups in question there are obvious formal, thematic and conceptual differences that make quite unconvincing the assumption that Čelebonović produced them either at the same time or suddenly turned from one working method to another, in other words, that they were created almost at the same time and in the same circumstances. On the other hand, since there is no list of works from the show in 1926 that could perhaps solve the dilemma terminus ante quem regarding the origin of the paintings from the Museum of Contemporary Art, nor, are there more precise evidences, it is not possible to draw a final conclusion.

(Complete text in printed edition)