Nevena Martinović

THE WORD AS FIGURE IN THE WORKS OF MILAN BLANUŠA

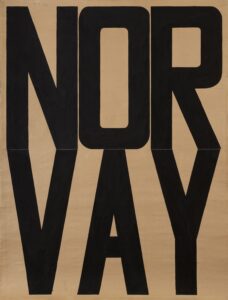

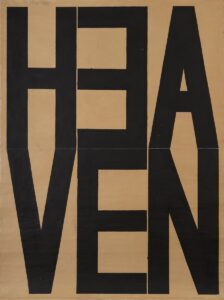

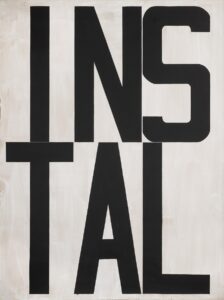

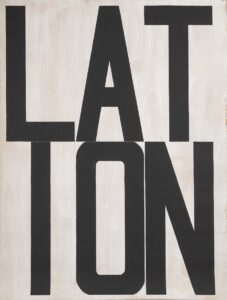

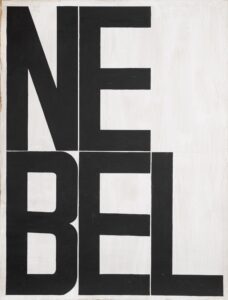

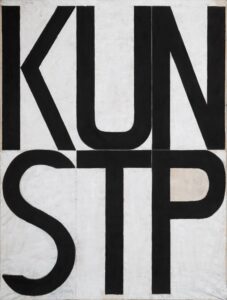

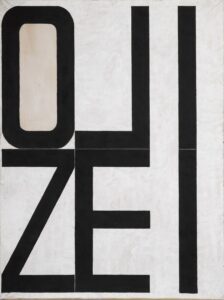

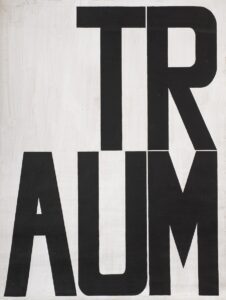

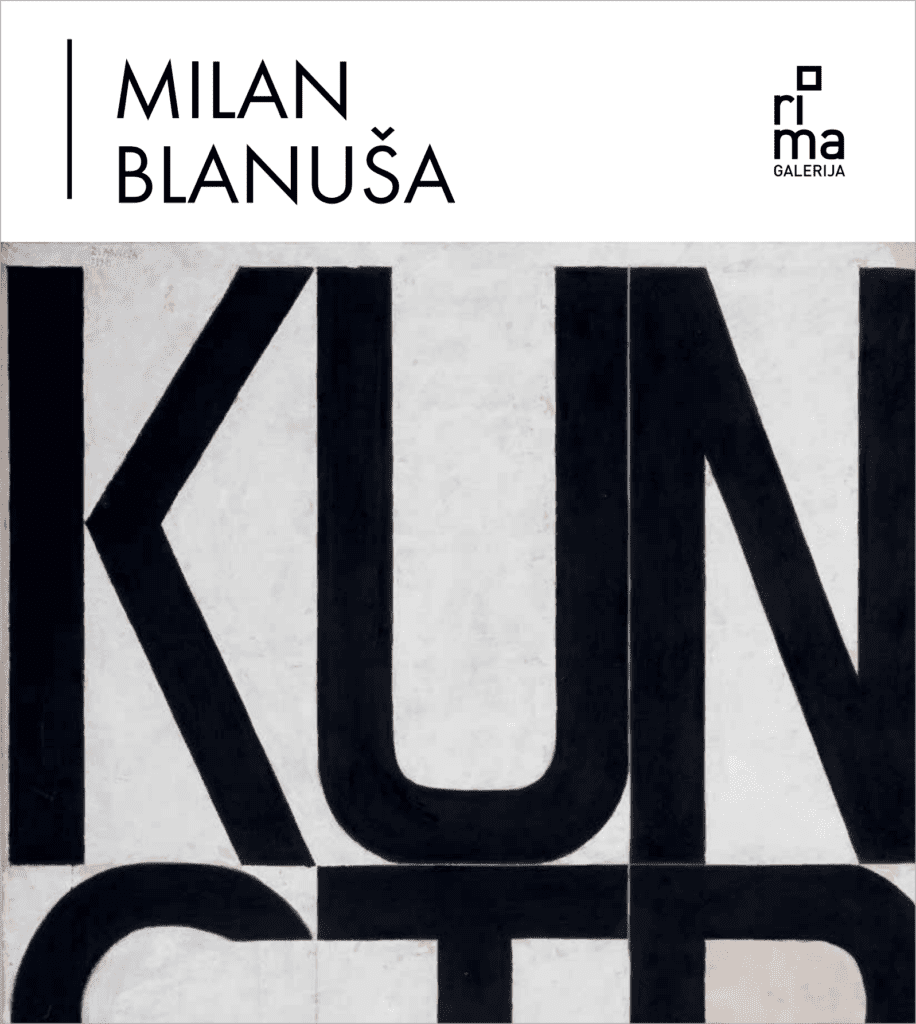

Between March and June 1999 Milan Blanuša produced a series of artworks that would soon become a unique episode in his overall opus. The word appears as the only motif of those drawings. Painted in black on big format paper sheets (200×150 cm) the concrete word strikes the observer first as a monumental and geometrically structured composition. Divided in two rows and oriented towards the visual compositional logic instead of grammatical, there are words in German and English: TRAUM (dream), HIMMEL (heaven), NEBEL (fog), BLITZ (lightning), KRAFT (strength, power, force), NORVAY, INSTALLATION, IDEE (idea), STREIK (strike), KUNST POLIZEI (art police). Until the exhibition in Gallery RIMA, more than two decades after they had been created, the artist had not shown these drawings as an integral series and for that reason this is a retrospective opportunity to re-examine the position these works hold in Blanuša’s opus. The main characteristic of these drawings – a decade long continuity in Blanuša’s painting – is the use of textual inscription in the picture, in German and the English languages. However, what becomes evident at the first sight is the fact that the text has become the only motif of the picture, the only carrier of content and form. Having in mind just that one element as the spot of transformation in Blanuša’s work, this series stands for several important issues: What is the role of text in Blanuša’s pictures, and has it changed in these works? What is the motivation of this creative episode, and has it had any influence on artist’s later creations?

There are numerous networked channels for a textual inscription to find its way, reason and justification for its constitutive place in Blanuša’s art. First of all, it is partially known that in his youth in Vršac Blanuša was extremely fond of literature and philosophy, that his life has been marked by his friendship and cooperation with Vasko Popa, that he was engaged in writing himself, primarily in the field of art criticism and essays. In addition, it was very early that text entered Blanuša’s view as a segment of socially turbulent and media transformed reality. At the fifth year of his studies in Belgrade, in 1967, Blanuša painted scenes of demonstrations with prevalent motifs of numerous heads and posters; those compositions drew the attention of the visiting professors from the Academy in Braunschweig. Then came the years of his master studies in that German city, during the period when the art scene of Europe was marked by new figuration and when turbulent social happenings, escalating in student demonstrations, were the catalyst of various forms of new artistic practices assuming that “the artist was speaking for himself”. As a student in Braunschweig Blanuša painted inspired by Gerhard Richter’s formalism and at the same time took part in the student “occupation” of the Academy in 1968, he had information about the actions of Immendorff and his informal group Lidl, got to know Beuys on his visit to the Academy. Those circumstances reveal the position from which the artist began to work on his own creative profile. In the changed context of new figuration and the original source in photography he chose the traditional painterly medium (drawing, painting, graphic print) and the picture as representation. Within this objectivity Blanuša accorded the human figure the central place from the very beginning. Simultaneously, due to the fact that he witnessed extensive social happenings where artists had to find out their own roles, Blanuša strengthened his affinity for works that provoked the individual as a social being, and desired that his paintings were not just sterile scans of social pathologies but carried inside a sting that could stimulate the beholder and waken up potential resistance. Blanuša found that the closest to his views were those fractions of new realism standing on the socially critical line of German art, with departure points in the works by artists belonging to the group Die Brücke and, later, artists from New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit). This is confirmed by his master thesis dedicated to the works of Max Beckmann and the fact that his paintings from the late sixties and the first half of seventies were very close to the poetics and aesthetics of the group Zebra with whose members he exhibited in Germany.

As a student of painting in Braunschweig and later, during the specialised graphic print studies in Frankfurt, Blanuša was a reporter from Germany for several local papers (Stražilovo, Književna reč, Omladinske novine) and published precious texts on current events at the German artistic scene. He actively followed and analysed the phenomena he saw at exhibitions in Braunschweig, Hannover, Kassel, Köln. In the years between his sojourns in Germany and in parallel to his first participation at exhibitions, he published critical reviews about significant shows, authorial and solo exhibitions in Belgrade, but also in Zagreb and Ljubljana. When he returned to his homeland permanently, after the studies in Frankfurt and his firm inclination to hyper-realistic poetics, he ended his art critic’s engagement and concentrated on his painterly and pedagogical commitments. After he had abandoned writing as a form of his confrontation with reality in the period when he painted hyper-realistic scenes of enigmatic atmosphere, Blanuša missed the precise targeting of reality with sharp expressions which he had used in his texts. Searching for an equivalent of such an expression in the framework of painterly figuration, he arrived at a new model of picture in the mid-eighties and this time text played an important role in those paintings.

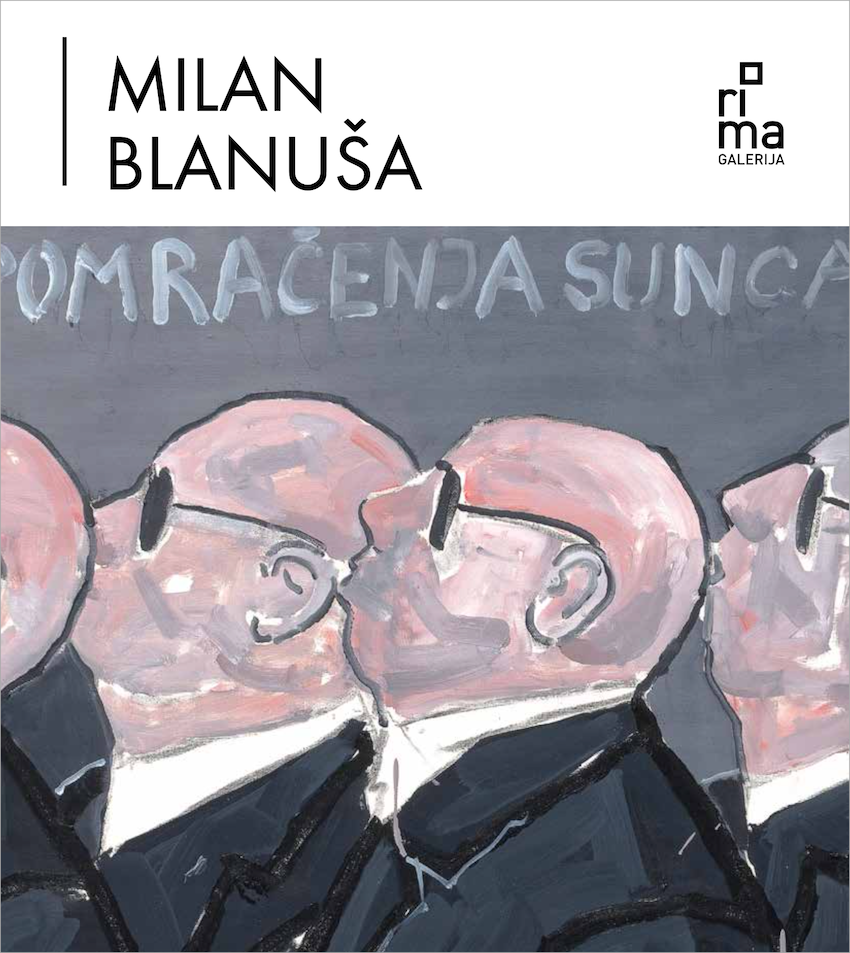

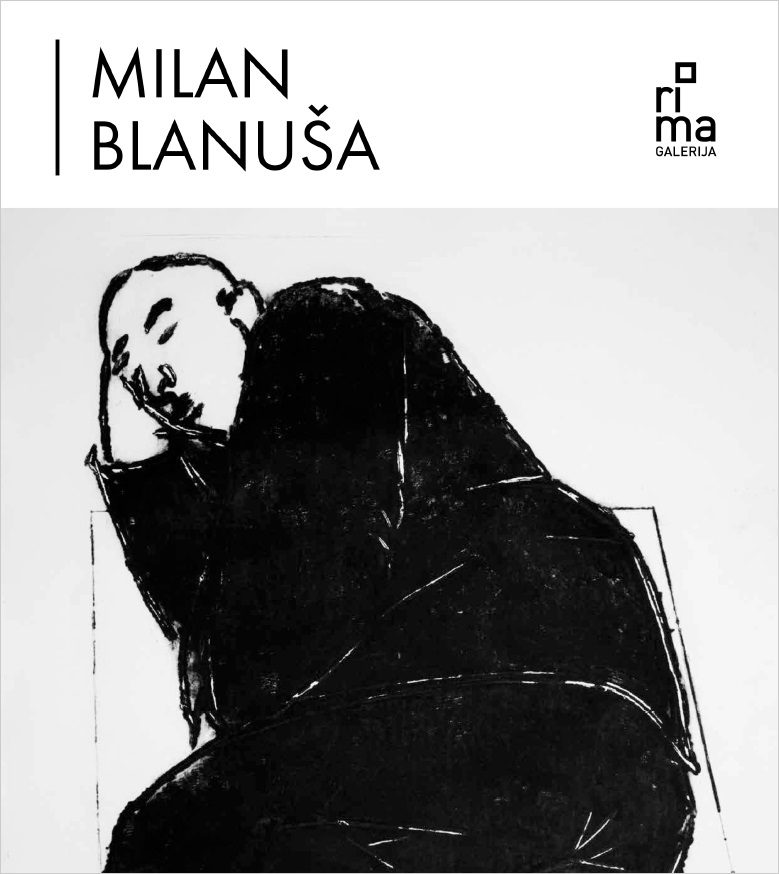

The development of postmodernist pluralism in the 1980s (and the climate of artistic appropriations) suited Blanuša’s solitary individuality to turn again towards his old, fundamental fascination with German art from the beginning of the twentieth century. In his reliance on historic phenomena, Blanuša’s choice synthetised raw expression on the level of human figure morphology, following Die Brücke, and the sharp, disfiguring view of reality, as with the painters of New Objectivity, Grosz, Dix, Beckmann. The tightening crisis in Yugoslavia brought Blanuša into sharp confrontation with the same problems German critical line of art developed – social deviations of the present time and intimate-public spaces in the city as stages of value metamorphoses. In preserving his departure points in photography, Blanuša developed a different figuration and scenes. At the same time, he performed significant experiments in the medium he was engaged in (such as the application of a grinder in the graphic dry point technique) and that affected the character of the line and the creation of a new type of drawing, essentially conformed to the artist’s need for “northern” clarity and precise communication. In parallel with these changes, Blanuša introduced textual statements in his pictures. Secondary to the figure as the carrier of the scene, in formal way, text appeared in the background, just like the graffiti on the walls or tiles in public lavatories, while in other cases the text was written with no particular visual motivation, differently oriented and positioned, although its position definitely pointed to the figure. Blanuša’s model figures of men and women came from the pages of daily newspapers, from black-white documentaries where photographs and titles in bold equally (trans)ported the breaking news. At the same time, Blanuša warned of an important influence of graffiti art on his painting: “Graphite not only as procedure, tool or material, as a spray-bottle, air-brush or crayon on the wall, but as words and messages that appear in my pictures and drawings.” The figure and the text are in symbiotic relationship, so that only by their networking one can understand the content of a picture. However, the metabolism of such a relationship is extremely ambivalent: “Those texts are frequently disparate to the happening in the picture and their goal is to bring the observer into a dilemma.” The object of Blanuša’s manipulation are in reality the expected and already coded meanings which the observer relates to written concepts. Let us consider the inscriptions (or titles) Predator or The Space of a Predator which, placed in the context of male-female relationship, indicate a scene of compulsion, aggression and resistance, suggesting physical and psychological aggression of a man over a woman. In front of those representations of a man in suit who is either alone on bed or in company of a naked woman, with whom he realises a passive sexual act or just watches television, the written words leave the observer’s expectations unfulfilled and awaken the feeling of frustration and unclearness. In the act devoid of passion, the man realises his biological instinct without pleasure, and the woman, probably paid for his pleasure, remains equally devoid of any human experience, including even the tiniest provocation of humiliation which the observer might have imagined. Aggression is, just like passion, deeply passive, repressed and exhausted, so much that in a hotel room it leaves behind only the atmosphere of “foolish sensation” and unnecessary dull uneasiness. The disastrous quality of Blanuša’s Space of a Predator lies in fact in the metaphor of contemporary alienation and emotional impotence, intellectual and spiritual dullness, a paralysed intimacy and empathy, a degeneration of individuality for the development of herd-like docility, an absence of selfhood. Owing to the text he uses, Blanuša is playing with the observer’s expectations, he first takes him into the trap in order to make him change the logic of “reading” the picture and find the way from confusion to a true reply. However, regardless of this important signpost role of the text, the picture will keep its primacy, accepting and recognising it as a partner of the figure, but still within its own framework and its own rules. Nevertheless, in the series of drawings with the image of Max Beckmann (1995) Blanuša cancelled the most elements of his scenes (the narrative, the space, light, colour) turning the drawing into a void that apostrophises the equality of the figure and the text. Starting from Beckmann’s photograph, Blanuša treats each drawing like a frame of Beckmann’s gloomy contemplative state whose anxiety is expressed in facial grimaces while the content is written above his head. The words in the German language, mostly taken over from the titles of Beckmann’s paintings (Redemption, Liberation, Departure, Dream about America, Dream about Germany, etc.) serve as interpretations of the meaning of appropriation and the use of the famous German artist in Blanuša’s picture. With these drawings, Beckmann was inaugurated into the symbol of exile, departure, deep existential crisis, which artists from these regions also felt in the 1990s.

In the three months of NATO bombardment of SR Yugoslavia in 1999, the artist produced big format drawings where the text is first formally (in its dimensions and the place in the picture) equalised with the figure (Urban I, II, III, Urban-Rubber Lovers) in order to suppress it and become dominant (Up, Down, North, South) and finally push it out of the drawing where it is the only motif. Blanuša’s choice of concrete words came, as he himself says, from “the overall situation happening in these regions” – from economic and political crises, over the tragic civil war, sanctions, general devastation of values, unsuccessful attempts of resistance and struggle, to the bombs that killed ordinary people and demolished the country. Therefore, one should not have any suspicions that in these drawings, produced in the period of three months of the most acute existential tensions, Blanuša adjourned the central place and monumental form to the words of specific meaning. It is almost impossible today, and perhaps unnecessary, to understand those meanings which forced the artist to choose exceptionally abstract and complex concepts such as: Dream, Idea, Paradise, Fog, Installation, Lightning. That search is perhaps the simplest in the case of the only geographically defined concept – Norway, of which the artist speaks with enthusiasm: “I have dreamt of the north and Scandinavian lands. When I was young, I desired to go to Norway. I have always been fascinated by Scandinavian philosophy (let’s say Kierkegaard) and literature, to mention only the Nobel Prize winner Hari Martinson. That northern spirit and the metaphysics of the north have always stirred in me some idea about freedom. I believe it is a country with a freedom-loving spirit and democracy”. This quotation and the two concepts from the series of drawings (Idea and Dream) clearly indicate that for the artist Norway is not a place on the map but a compilation of ideas and ideals to which he himself is striving and which support his own relationship to life and art. Within the same framework one should look for the sources of those drawings, chosen and gathered in an existentially sensitive and tense moment of personal and collective existence.

(Complete text in printed edition)