Nevena Martinović

MILAN BLANUŠA

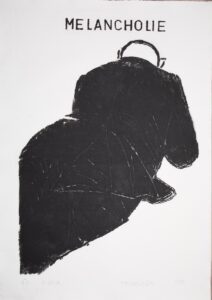

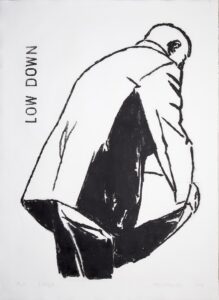

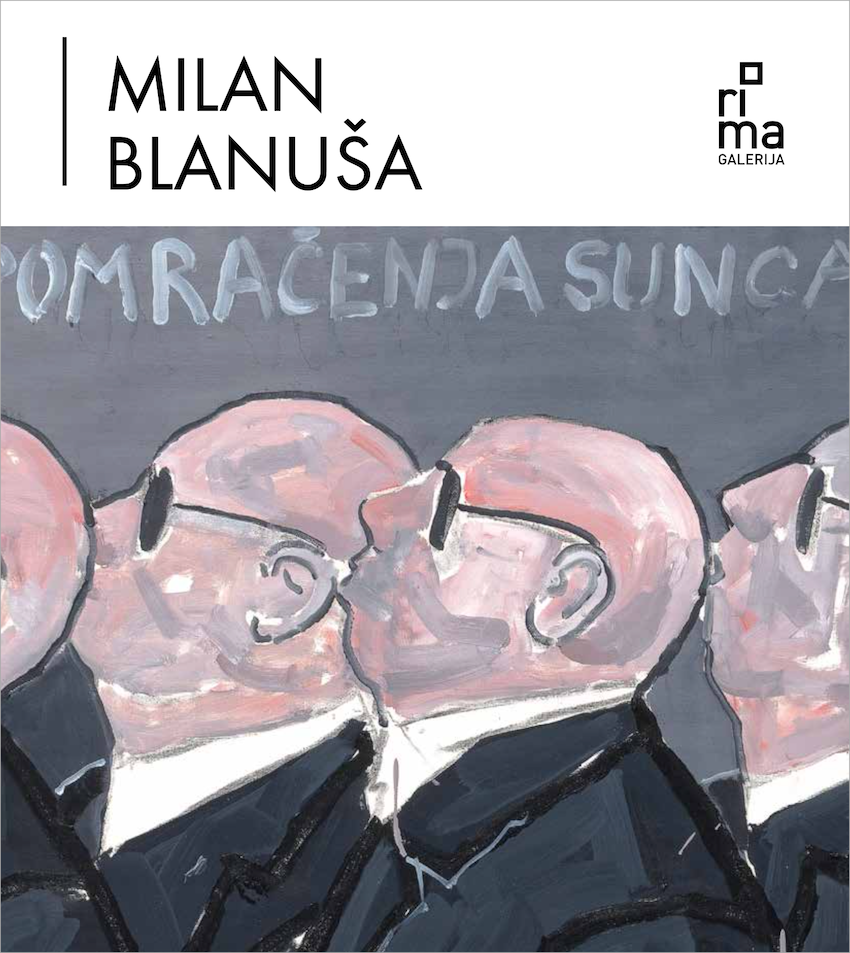

In the late 1980s Milan Blanuša reached his full creative maturity and in the following decades built a conceptually and hand-wise unique opus realised simultaneously in different media – from the drawing, over prints to the sculpture. His signature became a full and heavy black line which, as a visual art element, has a strict priority for Blanuša. He endowed the line both with a structural role and the role of an expressive gesture. By rejecting the extensive perfect finishing touches of realism[1] by means of a deeply incised black line, the artist dedicated all his attention to the raw essence of representation. Man has always been in the centre of Blanuša’s works, and since the late eighties his figuration has rested on the male figure of specific morphology. Dressed in a dark business suit, with white shirt and a black tie, this bald-headed man most frequently has an ordinary and unrecognisable physiognomy, also often hidden behind dark glasses. By creating and developing this specific humanoid type Blanuša was thinking about man and his overall degradation in the conditions of contemporary society.

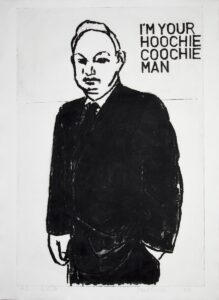

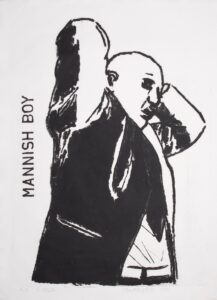

Text carries an important role in the basic concepts of Blanuša’s work. Although the artist respects the authentic nature of language and in his works texts are read as texts and not as primarily visual forms with textual content[2], the meaning of his words is supported by an inseparable connection with the painted motif. On the conceptual level, the text and the image in Blanuša’s works establish a commensurate relationship, contrary to the relationship of domination that would consequently lead to an illustrative image or a descriptive text. The character of this relationship is changeable and moves from complementarity over a tense opposition to total absurdity, but its function is always to decode the central idea of the work. “The title and the representation are in disparity. It is very important for me to produce a picture that would not illustrate the text, but to make the text emphasise the quality opposite to the one carried by the painted motif”[3], underlined Blanuša when speaking about two of his recent prints selected for his exhibition in Gallery RIMA. In the prints entitled I’m Your Hoochie-Coochie Man and Mannish Boy the visual and verbal language stand in semantic opposition. We recognise Blanuša’s men in suits: the first one holds his hand in the pocket with a blunt gaze towards us, while the second seems to be lazily stretching, holding arms behind his head. The texts written by their figures refer to the two blues standards of the same title from the 1950s. Both legendary songs by Muddy Waters, obviously in the sphere of Blanuša’s taste in music, speak of a specific type of man indicated in these popular lines with an expression difficult to translate – hoochie-coochie man[4]. Namely, Waters sings about a man born under a lucky star who becomes, thanks to the favours of the voodoo magic[5], a socially and emotionally unrestrainable individual[6] and lives his life freely, exclusively according to his own rules. Irresistible in his over-indulgence he imposes himself with his sexual potency as an alpha-man and great lover[7].Unexplainably charming and magnetically attractive, passionate in living and self-confident in appearance, at the same time crude and coarse – hoochie-coochie man is a radical hyperbole of individuality. “He is everything this painted one is not”[8], Blanuša commented briefly, with a smile, while looking at the figure on paper.

_____________________

[1] In his early formative period, during the seventies, Blanuša chose photo-realism, most frequently in the drawing. This early choice was influenced by his stay in Germany – first at M.A. studies in Braunschweig 1967-1971, and subsequently at a special course in graphic print art in Frankfurt 1976. Already as student, in the atmosphere of several ongoing artistic tendencies in Germany, Blanuša turned to the photorealistic drawings and discovered the work in graphite pencil as his own medium. In this period he produced photorealistic portraits of artists (such as Magritte, Picasso, Bacon) as well as of human figures in movement he placed into an eerie atmosphere of void, suggesting by that the existentialist feelings of absence and privation. He had his first solo show of those drawings in Braunschweig, and later in Belgrade. One of the works from this photorealistic phase won him the October Salon award in 1978.

[2] The paintings in which the artist conjures up the ambience of a bathroom or only indicates walls in the background (made in the nineties), contain a written text as an integral part of the scene. There the text obtained the visual identity of graffiti. However, written messages appear as independent entities in many paintings – they are not part of the painted scene, but as parts of the painting they have the task of semantic decoding. In Blanuša’s works the text retains the authentic nature of the language as a means of verbal expression. This is particularly well confirmed in the series of graphic prints and paintings entitled Make-up, Shaving, or Putting on the Tie, where Blanuša quoted sentences from the texts by two conceptual artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss – in other words, from a conceptual artwork that insists on the autonomous nature of language as a verbal transmitter of the idea of free artistic modelling.

[3] Interview with Milan Blanuša, held on 4 July 2019 in the artist’s studio in Vršac, as part of preparations for his exhibition in Gallery RIMA. A transcript of the conversation is kept in the archives of Gallery RIMA.

[4] „Hoochie-coochie“ was originally the name for an erotic dance, particularly belly-dance, and for the dancers who performed it at village fairs in America. In time it has become a slang expression for a lascivious, sexually overly liberal and insistent woman. Nevertheless, in the popular verses of Chicago blues, including those sung by Muddy Waters, a „hoochie-coochie“ man loses all negative connotations. They describe a man who becomes an irresistible lover thanks to his own luck and voodoo magic. His sexual love-triumphs are at the same time the cause and consequence of his feeling of self-confidence, independence and domination over life and destiny – of those feelings that pervaded the desire of Afro-Americans for human and personal freedom and social equality in the 1960s.

[5] I got a black cat bone / I got a mojo too / I got John the Conqueror root / I’m gonna mess with you / I’m gonna make you girls / Lead me by my hand / Then the world’ll know / The hoochie-coochie man (…)

(Muddy Waters, I’m Your Hoochie-Coochie Man, text Willi Dixon, 1954)

[6]I’m a rollin’ stone / Man-child / I’m a hoochie coochie man / The line I shoot will never miss

[7] When I make love to a woman, / She can’t resist (…)

(Muddy Waters, Mannish Boy, text by Muddy Waters, Mel London, Bo Diddley, 1955)

[8] Interview with the artist. See reference 3.

With his strategy of semantic oppositions Blanuša indicates the possibility of defining human representations in his pictures by what they are not and what they do not have. In the centre of this negational definition stands the absence of the essential quality of a hoochie-coochie man – the freedom in every aspect of existence. The typic appearance of Blanuša’s figures, their ordinariness and their unmemorable physiognomies, together with the dull dress-code as a class symbol of the political-corporate caste, indicate insufficient freedom of thought, decision-making, speech and behaviour. Each individual characteristic is censored, first by the system that remodels them and then also by self-censoring that turns into the steps leading to the top in their hierarchic ascent. Once they have successfully grown into their suits censorship becomes meaningful because memory of freedom has been erased and personality removed forever. A lowered, absent or repulsive gaze, the sluggishness of the figure whose movements suggest inaccessibility and disinterestedness (hands in the pockets, hands crossed on the breast, back turned towards the beholder) – all those are indicators of protracted degeneration – emotional and physical castration as a symptom of final dehumanisation. The man in the suit lacks everything a hoochie-coochie man has at his disposal. As an opposite of uncontrolled freedom and life energy, Blanuša’s figure is a metaphor of man’s self-annulment: from the cancellation of all specific features of an individual to the extinction of emotional and sexual potentials as universal characteristics of man. From cancellation of the self to cancellation of humanness.

The artist finds models for his works in daily newspapers, in the figures and poses of politicians and businessmen, small and big mercantile fish, local and global leaders. Blanuša appropriates as important elements of his outlines of men in suits the poses recorded by newspaper photographers, from nonchalant postures to hearty handshakes and embraces. This documentary approach, so evident in the directness of postures and gestures, and particularly stresses in black/white prints, reflects the connection between men in suits and social reality. Although emotionally empty, Blanuša’s humanoid figures use a repertoire of gestures that express diverse feelings, such as heartiness (handshake), friendship (embrace) or intimate love (kiss). Alienated from internal causes and instigations, these gestures appear in Blanuša’s works as parts of mimicry that makes the usual gestural communication a means of manipulation with identity. In the essence of this signifying quasi-language lies hypocrisy as strategy of the rulers to disguise into the people they rule. with this chameleon-like skill – not to understand but to imitate well, not to belong but to fit in – big and small pawns of the capitalist order manipulate individuals by abusing communication symbols charged with significant emotional concentration.

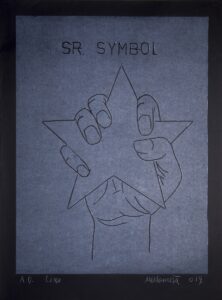

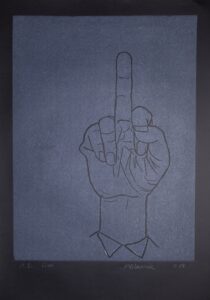

Although there are among these non-verbal messages those that communicate socially acceptable and positive feelings, man in the suit occasionally makes a more radical choice. The best examples of power, of the use and abuse of language (in this case gestural) are Blanuša’s sculptures Serbian Idol and Symbol – there is a non-verbal insult in their epicentre, better known as “the middle finger”. In the history of Western civilisation, a hand with the middle finger raised, many times magnified in Symbol and standing dominant like a trophy, has been transformed from a sexually loaded curse into one of globally most recognisable symbols of revolt. This non-verbal slang is not only an insult but it also indicates specifically an individual who is capable of crossing the border between the socially acceptable and individually necessary. The middle finger is raised in the moment of self-proclamation, when one places himself before the others, rejecting all good manners and social considerations in order to give freedom to repressed resistance. The finger is the ultimate gesture of the hoochie-coochie man who resolves to be rejected and scorned like a crude person in order to fulfil the imperative of his feelings (his anger and opposition). Therefore, Milan Blanuša sculpts this insolent phallic symbol as if sculpting a portrait bust. The huge hand that structurally holds the position of a portrayed head is modelled together with its plinth. The finger on the pedestal looks like a sculptural metaphor of crude resistance in each of us, the resistance we have suppressed many times for the sake of social conventions.

However, the content of Blanuša’s works is never unidirectional, and his man is always a reflection of the state of social microorganism. With one, seemingly formal detail, such as the jacket sleeve, Milan Blanuša directs the content of the work towards the gestural vocabulary of his men in suits. In his sculpture Serbian Idol (2008), Blanuša’s humanoid figure, neatly dressed in his suit with a tie, raises his hand high and directs the middle finger upwards, towards the sky. He uses the gesture that can be read as an extreme expression of spite – a feature colloquially considered characteristic of the Serbian people- On the other hand, seen from under the shelter of good manners and human decency, to which Blanuša also belongs, the middle finger is an exaggerated act that appears in the moments when one is staggering with one’s personal freedom. Namely, in the social circumstances present in Serbia for decades, an ordinary man is frequently forced by hopeless life situations to slip from good manners into verbal or non-verbal crudeness. The middle finger, seen as an epitome of every curse, has become a firecracker of vulgarity and its short explosion relieves the pressure in emotional valves. Although it has been primarily a manifestation of profound social crisis, that vulgar gesture is simultaneously an indicator of the stubbornness of human individuals who refuse to despair or surrender. It is the last sign that adrenalin reservoirs of survival are active, social patterns rejected and the steering wheel of existence has been left to instincts for just a moment.

Attentively observing Blanuša’s Serbian Idol we see a man in suit who has raised his middle finger and thus stepped out of the zone of political and educational correctness and revealed himself as one of us. As one who, confronted with numerous obstacles, sends out the message that he does not care and that he will succeed in spite of everything. Moreover, he is so self-confident that he directs his phallic sword high upward defying with it the invisible powers which control the entire physical and spiritual universe. An ordinary man, under the pressure of existential troubles stays hypnotised with the raised hand whose height, seems to him, is proportionate to the self-confidence and courage of one man. That hand resembles his own, but instead of pointing to another man it has been raised much higher and the middle finger reaches much farther. Serbian Idol gestures spite and defiance, and not only towards a visible enemy but towards the heaven and invisible powers, towards God himself. With this simple gesture the small corporate clone presents himself as a stubborn person and a rebel who turns over a new leaf and takes his life in his own hands. By means of this effective mimicry drill the political puppet is represented as a hoochie-coochie man who victoriously manages his own destiny. The success of the quasi-humane social and economic order, realised by the abuse of powerful communication symbols, lies in the faith afforded to it by ordinary people confident that they link their own destiny to a charismatic personality most free and most defiant of them all. Therefore, when we attentively observe again Blanuša’s Symbol that seems to be a monolithic version of the Serbian Idol’s hand, we are re-examining the sincerity of the use of “the middle finger” and doubt our initial impression about its rebellious meaning. Then, with an almost bitter smile, we ask ourselves: Is it our hand or a hand directed towards us.

In Blanuša’s overall opus, from the earliest student works produced in the late sixties, over photo-realistic drawings from the seventies to his mature creations and the latest prints exhibited in Gallery RIMA, the morphology of the human figure is his visual comment on the state of social micro-organism. Since both causes and consequences of all social conditions are contained in man, on the local and global levels equally, the artist outlines his criticism of the society through his critical approach/outlook/view of man. With his works he informs the diagnosis of what a social being is suffering, the illness that has achieved pandemic state. Men in suits are not personalities taken from the daily political scene, but metaphors of the infection caught in the conditions of political, educational, cultural, ethical, aesthetic and every other spiritual unhygienic circumstance. Blanuša’s criticism, therefore, does not except any observer – the artist much more readily offers us a chance to re-examine our own roles and responsibilities in the social micro-physiology of our social environment.