Ješa Denegri

THE ROLES OF MIODRAG B. PRORTIĆ IN SERBIAN ART IN THE 1960s AND 1970s

The three, closely intertwined roles of Miodrag B. Protić – as painter, art critic/historian and organiser of artistic life – in Serbian art of the 1950s continued and progressed in changed conditions in the two following decades (1960-1980), both in his own artistic development and in the surrounding socio-political and cultural context. Those were the decades of numerous remarkable data in his artistic biography when he, as a painter, received new recognitions – from the award at the 1961 Triennial, his solo show in the Salon of the Modern Gallery in 1962 (on the background of attacks on abstract art organised by highest political officials in early 1963), followed by his participation in Yugoslav selections at international exhibitions, such as the Third Morgan’s Paint Rimini (Italia-Yugoslavia) where he got the gold medal, then in Tate Gallery in London, in the Museum of Modern Art in Paris, Rome, Milan, Stockholm, and also his participation in the Sao Paulo Biennial in 1965, his solo show in Athens in 1966, the solo show in the Gallery of Contemporary Art in Zagreb and his joining the Group 69 in Ljubljana in 1969. In 1966 he was elected a corresponding member of the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts (JAZU Zagreb, together with Milunović, Lubarda and Aralica). In the first half of the sixties Protić published his theoretic book Painting and Meaning (1960), and the second volume of The Contemporaries (1964). However, the crucial event in this decade of Protić’s activity was certainly the opening of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade, in October 1965, with the first authorial permanent display as the crown of his engagement in the founding of the Museum, his conceptual justification and organisational leadership of that institution, following the experience he managed to gather during his study sojourn in New York and apply to the specific features of local cultural and artistic circumstances. However, all of the mentioned are only the most essential, but not complete data about Protić’s simultaneous triple activity performed in almost everyday roles, duties and jobs of his public and professional engagement.

In the well-known dispute with Grga Gamulin in 1955 about the legitimacy of abstract art in the period immediately after socialist realism, Protić revealed his theoretic conviction that the notion of abstraction in painting was not in irreconcilable opposition with the existence of references to objects, as was contained in his thesis about harmonising the “trinomial line-colour-object”. Thereby, the concept of “object” did not assume a representation of a concrete real form but was reduced to sign allowing for the possibility of representing not only material but also immaterial phenomena of nature. Namely, while in the 1950s the object in Protić’s paintings was treated as a thing (according to the titles such as Lamp, Mandolin, Shell, Aquarium etc.) in his paintings from the early sixties and later the concept of object referred to untouchable and unreachable forms such as Sky, Moon, Constellation, Asteroid etc. as represented in the titles of his individual paintings or even whole cycles. In that way, a painting did not describe an object but became a metaphor, a symbol, a sign of the objectness that had no longer any support in the world beyond the painting but existed as an objective component within the “trinomial” where the other two elements, as qualities of abstraction, were understood to be the categories of “line” and “colour”.

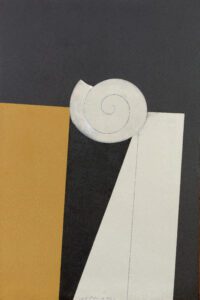

By conducting in his own paintings the process of reduction from the representation of a material object to a sign of non-material form, Protić established his theoretic thesis about the existence of the “semantic key” – in his interpretation of his own painting it assumed “the reduction of an object to a geometrical sign (shell-spiral, asteroid-circle, sandglass-triangle) incorporated into the concept of whole as an essential element… In fact, that kind of reduction followed the ideal of totality, believing that even fragments of the world could reflect its whole, and the breadth of life could be conceived by making one of its manifestations universal”.

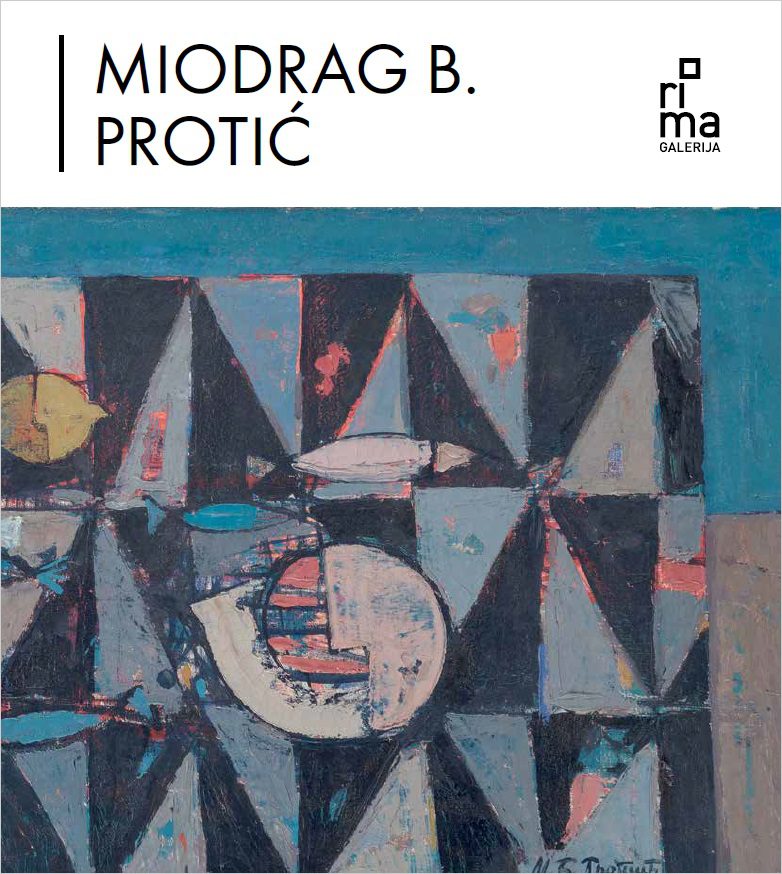

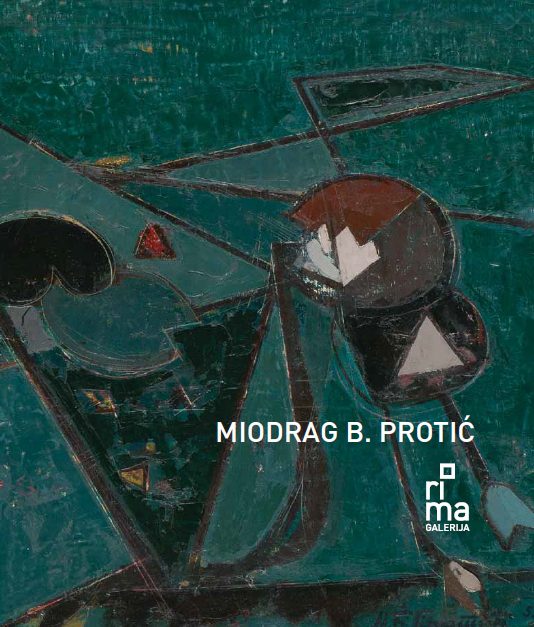

Protić adhered to this basic conceptual constant although in some visual elements and technical procedures it underwent certain changes in the sixties. It is obvious that paintings from the early years of this decade (for example the two version entitled Studies I and II, 1961) reveal, notwithstanding the essential compositional principles, traces of free and direct application of paint and could be interpreted as concurrent and transitory consequences of their origin at the time of the then fashionable informel, an artistic movement foreign to Protić and even opposite to his understanding of art not only because of a different painterly sensibility but also from the basic ideological position.

In the sixties and early seventies, Protić conceived and realised as the Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art a series of exhibitions dedicated to different decades of modern Yugoslav art: Third Decade – Constructive Painting, 1967, Surrealism-Social Art, 1969 and Fourth Decade – Expressionism of Colour, Poetic Realism, 1971, and then, among other things, he made the first revalorisations of the local movements of historic avant-gardes – the Zenitism of Ljubomir Micić, the Dadaism of Dragan Aleksić and Belgrade Surrealism. The concept of these exhibitions devoted to the art of the 1920s and 1930s clarified Protić’s understanding of the notion of “Yugoslav art” as the art of the then common sovereign state with a particular concern for the specific features of certain national cultural environments, as confirmed by the fact that experts from Croatia and Slovenia were invited to analyse local art as the most competent connoisseurs. His concept of “Yugoslav art” was neither “centralistic” nor “unitary”, or prone to the recidivism of “integral Yugoslavism”; on the contrary, his concept was pluralistic not only in accepting different artistic expressions but also in honouring the right to local national cultures, and one of them was Serbian art in the period between the two world wars. In the eighth chapter of his Noah’s Arc, dedicated to the period 1961-1965, Protić quoted a very symptomatic episode about the dispute between Dobrica Ćosić and a group of Slovenian intellectuals related to the organisation of socialist Yugoslavia, by expressing his own adherence to the current standpoint of Ćosić.

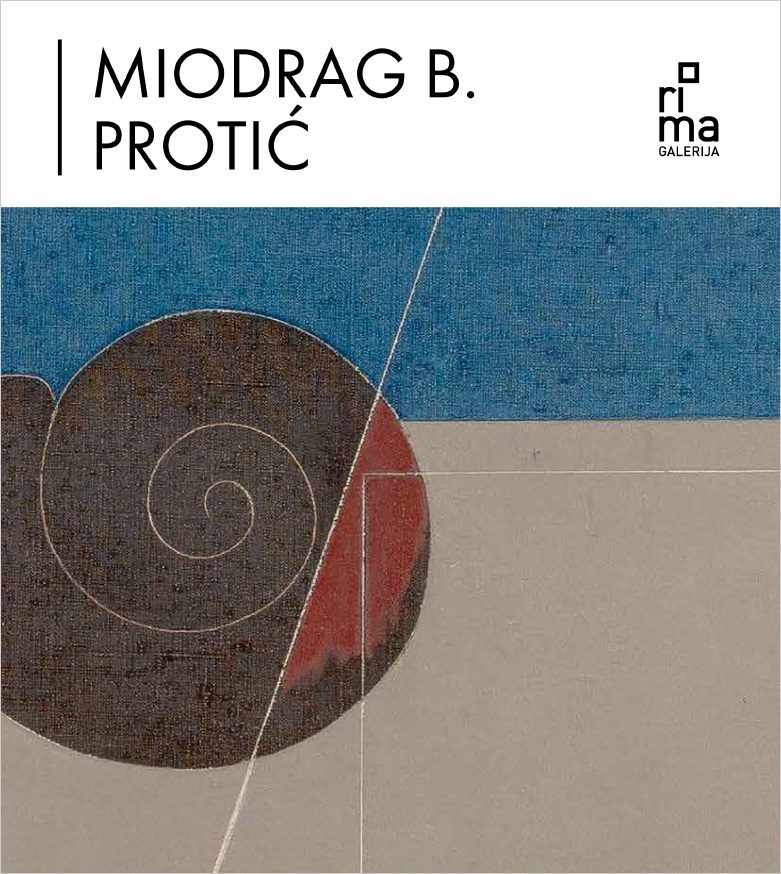

A controversial but frequently used term “abstract landscape” was introduced to denote one of the widely spread post-war interpretations of abstract painting with sources in experiences of nature, after the title of Aleksa Čelebonović’s 1961 exhibition in the Gallery of the Cultural Centre in Belgrade – Abstract Landscape, where Protić was one of the participants. The mentioned term had its origins in the genuine concept of paysagisme abstrait created by the French critic Michel Ragon. Protić believed that “imaginary spaces” was a more adequate denomination for his version of this painterly view – the concept was related to a cycle of big format paintings exhibited and well-received at the Biennial in Sao Paulo in 1965. The dominant element in those paintings was the motif of circle as the moon in the upper part of the canvas and a uniform dark surface as representation of land in the lower half of the painted field. “Imaginary spaces” referred to the fact that in that type of painting forms were not the existing and proven data from nature (moon, earth) but, in this case, also painterly entities of potential objectful qualities of some imaginary and non-existent landscapes. Protić defined this characteristic of his painting in the following statement: “… the circular form of the moon, yellow, white, blue, red or black, with a dramatic limbo, placed in the upper part, with impasto melting and falling like an echo of an explosion on lateral vertical margins. That link between the geometric and organic, between fantasy and reality was the link between heaven and earth or between concept and life”.

The painting that summarises the described process of gradual reduction of representation towards the sign and where that concept plays a major role is Gea (1969), a picture of exceptional status in the overall painterly opus of M. B. Protić, as confirmed by the fact that it was published in Gillo Dorfles’s book Ultime tendenze nell’arte d’oggi (1973). With regard to this painting and a number of those that treated related problems, created almost at the same time, their author quoted the following interpretations in the second volume of his Noah’s Arc (1969): “In the beginning (…) a somewhat geometrically reshaped object was incorporated in the structure of the painting, but it was material and materialised. After that, it changed and became a symbol, a sensitive semantic code…”. And further on, at a different place, he said that it was “an attempt to introduce the power of one’s personal experience into new spiritual needs… Innovation could be observed in the final reduction of the object, in the demonstration of the resources, in an almost purist syntax”.

The seventies were the decade of Protić’s intensive writing, painting and exhibition activities. He published the books Serbian Twentieth Century Painting I and II, (Nolit, 1970), Yugoslav Painting 1900-1950 (BIGZ, 1973) and the monograph study on Milena Pavlović Barilli (Prosveta, 1972). He took part in the authorial exhibition of Lazar Trifunović Abstract Painting in Serbia (1971), organised his solo shows in the Gallery of the Cultural Centre in Belgrade (1973 and 1976) and in the Gallery Forum in Zagreb (1974). In the wake of the thematic and formal solutions of his painting Gea (1969) he produced individual paintings and condensed drawings, mostly with the motif and symbolism of the shell, entitled Imaginary Landscape, Horizon, Eclipse of the Sun, Yellow Aquarium, Big Constellation and Big Constellation in Blue (1973), Composition with Shell and Constellation with Shell (1976), Shell (1977) and others, all the way to different versions of paintings entitled Signs of the Evening and Signs of the Night (1979). He then began the series of cross-like paintings-objects entitled In Honour of Malevich, continued to work on them until 1982 when he finished the series and recorded that those works “entered from the physical cosmic space into the spiritual space of human destiny”. In 1980, after two decades as head of the institution, he retired from the position Director of the Museum of Contemporary Art, and in September-December 1982 a retrospective exhibition was organised for him there; it was later moved to the Rihard Jakopič Pavilion in Ljubljana.

Protić spent the 1960s and 1970s painting and participating in other areas of his public activities, always with a permeation of ambivalent moods of almost idealistically faithful dedication to art, on the one hand of this irreconcilable span, and on the other, in his acute knowledge of the ruining of all other social processes. Namely, one can notice from the contents and the title of the eighth chapter of Noah’s Arc a suggestion of intolerable extremes: Sun in the Zenith, Thunderbolt in Sight, and also in the first sentence of that text: “The sixties… marked by oppositions, ripening and rotting, by external rise and internal decay”. When one reads again those pages of Noah’s Arc dedicated to the period 1961-1965 one can conclude that their author was already aware of an overall crisis of the ruling political order, particularly of its (non)functional pragmatic aspect qualified by a rapid rise of bureaucracy and its disastrous influence in all areas of social and cultural life. But, as an autonomous intellectual and primarily an artist, Protić looked for and found reasons and ways for his non-participation in those unacceptable circumstances not only in committed painting but also in his unselfish engagement – as historian and manager of the Museum – in activities advantageous for the mutual cultural prosperity of his own milieu. Above all, therefore, he believed in the lasting quality and permanence of art – in accord with the motto Ars longa he used as title for his retrospective in the Gallery of the Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts in 2011 – without ever doubting his faith in the pre-eminence of art above and ahead of all other areas and courses of unfavourable happenings around.

Artworks

- More about the artist