8 May - 8 June 2023

Nevena Martinović

Cinema Utopia. On a New Cycle of Perica Donkov’s Paintings

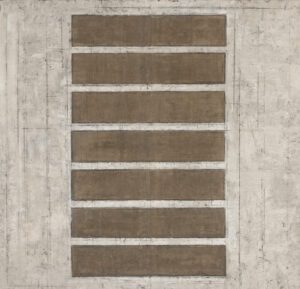

The paintings by Perica Donkov, produced between 2021 and 2023, shown for the first time in the Belgrade Gallery RIMA, are, in their general characteristics, results of the already authentic nature of Donkov’s painting. In their composition and structure they are purified to non-referential, reduced and geometricised (but not geometric) surfaces. His latest works bring simple areas with centres containing at equal distances seven horizontally elongated rectangular fields of identical dimensions and formats and in a precise vertical line. At the same time, as a balance to the „cold“ and almost minimalist structure, Donkov establishes an accentuated physical relationship towards the foundation (rough sackcloth again), by emphasising its robust expressive materiality. The third recognisable characteristic is the pre-conceived ambient distribution for the cycle as a whole – only after it has been adapted to the chosen space it can be completed on the formal and conceptual levels, this time in the display the artist himself entitled Cinema Utopia.

A distant suggestion of compositional solutions of the new paintings by Donkov could be sought in the work Painting as Shelter, the central work displayed in the Gallery of the Youth Club in Belgrade, in 1989. At this solo exhibition Donkov demonstrated for the first time a new dimension of his works – the „precise ambient distribution of works produced in the studio where the entire exhibition turns into a single work.“[1] The painting with heavy pigment layers and dense facture is imprisoned in a rustic frame made from massive wooden rafters with two of them horizontally placed over the painted surface, emphasising the impression that the painting was receding into another plane, closed and inaccessible. Seen from a distance, this work impresses one as an abstract painting broken with narrow ribbons in three horizontal rectangular areas. In the works shown at that exhibition, where the artist most radically confirmed himself as a protagonist of neo-informel, one could find a certain expression of the crisis[2] which could later, from a historic distance be read as an „intuitive indication of the event destined to happen in near future“.[3] Therefore, it is not surprising that a similar compositional formula, this time purified to a striped structure related to the latest works, appears in a sporadically executed painting of smaller dimensions at the very beginning of this millennium, in the difficult time marked by the effects of the NATO bombardment and systematic social crises of all values, from economic to ethical. In his works at the show Cinema Utopia Donkov returns to and remains at such a formal solution of the painting, extending it to seven parts and repeating it almost obsessively, as in a ritual that gradually revives him, bringing to the surface of consciousness what had been felt before. Nevertheless, in these non-referential pictures, as in the case of his previous works, life promoters of artist’s experiences and ideas remain hidden by fog in faraway suggestions. Instead in the direction of their concretisation, Donkov turns towards an even more radical abstraction – by translating the repetitive rhythm into the basic motif of the work as ambient display. Notwithstanding an intuitive or a totally conscious choice – the number seven in the foundation of artist’s internal dynamics of his new paintings has been represented in different civilisations and religions as a symbol of a complete cycle whose repetition realises different aspects of human life. As the top „symbol of overall motion, or comprehensive dynamism“[4] – number seven has almost ideally found its way into the centre of Donkov’s Cinema Utopia.

Each picture in the cycle has been separately executed and represents a separate whole[5] with geometric patterns repeated in the same way in another painting, then in a forthcoming one, wherever the observer turns, producing the illusion of loop rhythm where the interruption of the septimal pattern becomes almost impossible. Therefore, the goal is not, as in previous cycles by Donkov, to link paintings into a uniform visual art membrane that physically redefines the space and makes the observer wonder about the character of the ambience he/she has stepped in (quasi-sacred space, shelter, camp, deaf room, etc.). Rather, a repetitive visual frequency or septimal tact is established, so that the observer’s mind begins to resonate after a certain time spent in the space. As a consequence, the observer and not the artist or his work, is the one who defines the nature of the ambience he/she belongs to by means of his/her own established rhythm.

The regular rhythm in Donkov’s paintings easily attracts attention owing to man’s natural need to establish a structure in his micro-world. All the knowledge and skills appropriated by the method of repetition/restoration – from the first steps to the most complex scientific experiments – deeply root man’s experience of the world and can be changed or overcome only with great difficulty. A particularly significant aspect of repetition are ritual patterns, from those concerning simple everyday pleasures to complex mystical and religious processes because they direct their conductor’s baton towards the unconscious, emotional and spiritual. We patiently build our secure home with small and great rituals within the space of our own mind. That building from which we observe and measure the surrounding world, offers structure and clarity, the feeling of stability, comfort and control. However, repetition is a two-sided coin showing on its head the power to encircle us with walls and close our view to numerous possibilities behind them. Therefore Donkov, using the ambience of a paintings can multiply his septimal tact into an infinite repetitive rhythm, thus pushing it to the limits of the absurd – moving the principle of repetition from an appropriate mechanism to a self-sufficient goal. The visitor, overwhelmed with Cinema Utopia can define the final result of this small art experiment by Donkov – will the repetitive impulse receive its linear projection and astound the observer with its senseless infinity, or will that same impulse acquire critical acceleration and throw it beyond the borders of absurdity with its centrifugal force into „the possibility of imagining another reality, another value system“[6]. In final instance, as it has been mentioned before, this influences the character of ambience where the observer exists – whether he/she feels plunged into the atmosphere that lulls to eventual lethargy, or he/she may be in the environment that, provoking inconvenience, stirs the need for change. In this way Donkov’s latest cycle meaningfully positioned right in between these two extremes – between the wish for security and the instinct for freedom, between the need for a clear and structured world and the desire for the unknown, uncertain and exciting. Essentially, those are the polarities whose harmonisation rests in the core of every utopia, somewhat less in those personal and escapist and more in those collective utopias of reconstruction.[7] Donkov’s Cinema Utopia resembles the simulation capsule for possible states on both sides of inapprehensible balance. Only within it can we confirm again the absurdity of our endeavour to reach the utopistic state of harmony. At the same time we become aware that our penetrations towards that absurd represent in fact the only values of our lives – movements beyond the safe zones and getting acquainted with a completely new space of our own mind.

It has to be seen whether the artist himself intend to conclude with the new cycle a long chapter of his creation and then, saturated with his own rhythms, open the crack towards new researches. It is only in these works that two elements appear or, maybe, come back – two elements new in relation to his crucial works from the last twenty years – an extended chromatic scale and thin/transparent deposits of paint. The powerful blue monochromes exhibited in 1998 in the ULUS Gallery were a special swan song of the coloristic flourish in Donkov’s previous works – after the 1980s he self-consciously approached his palette in his abstract expressions and almost extatically indulged in painted scales within the area of a painting. Social and personal turbulences were to be refracted in Donkov’s creative works at the beginning of the new millennium. Between the bombardment of 1999 and the fire that completely destroyed Donkov’s studio in the fortress of Niš in 2004, the colour first receded into cassette areas (Amor fati 2001/2002) in order to disappear completely in coal-black tones of numerous cycles when the displays grew into synonyms of Donkov’s creative production – from his exhibition Glory box (2006), over The Fuge (2011) and Reconstruction of Room 12 (2011) to Deaf Room and Blind Faith (2019). However, in his latest works the artist steps again into the intensely blue nuances and permits them to occupy the entire space of the picture, having attributed to them the role of identifying. Donkov’s inclination to the deep tones of blue has roots, just like his entire opus, not in the perceptive pleasure or affinity, but in the fact that it is the colour full of symbolic layers throughout the entire history of culture, and mostly those related to spirituality, mysticism, eeriness; this time it perfectly corresponds with the symbolism of the number seven. The artist also introduces nuances of the red spectre – from earthly brown to dusty pink, colliding in clearly defined frames with the blue, creating new differences in the experience of the same compositional solutions. In the concept of the display, the changeability of colours from one painting to another has its particular role: it impresses one as a destabilising factor within a consistently unified rhythmic pulsation. Chromatic variations, as radical contrasts to the geometric patterns, influence the accentuation of the repetitive principle by strengthening its unbearable sameness. Colour is the artist’s preferrable disturbing factor which has found its way into the expressive layer of the picture, for such a long time ruled only by the crude materiality of the work.

Let us mention another important innovation which, as different from the colour, sporadically appears in the cycle and concerns changes in artist’s relationship to the foundation and the process of creation. In Donkov’s production, as much as a work cannot result from simple sensual sensations, it is also impossible for its content to be realised in a painting which is sensually impotent – which rejects its physical existence or is disgusted by its own materiality. Therefore, the authentic procedure of the creation of a painting, applied to the majority of works from the new cycle, emphasises its tactile physical dimension. The lamination of pigment on to unprepared sackcloth and a conscientious building up of structure is interchanged with its crude destruction, scraping, peeling, drying. The result is a surface tired of suffering, transformed by its constant resistance to the hand and (non)painterly tools. The roughness woven into each pore of its tactile existence is transposed to space, endowing the walls with the character in which they breathe, hear and address the gallery visitors. So, why do certain canvases contain light, transparent layers of paint that treacle down the surface of the canvas not disturbing its physical wholeness, without disturbing its barriers, without changing its material identity? If this formal change is a symptom of an internal step out, these pictures suggest with their relatively confusing diverse signals in relation to the whole, a possible new path in Donkov’s creative activity. The artist reminds us in that way for an umptieth time that the only rule confirmed by a saying is that this exception will interrupt the loop rhythm, break the existing pattern and be the first step in the future conquering of freedom.

[1] M. Prodanović, Perica Donkov. Slika kao sklonište (P.D. Painting as Shelter), Fondacija Vujičić kolekcija, Beograd 2015, 51.

[2] J. Denegri, Perica Donkov, predgovor u katalogu (exch.cat.), Galerija Doma omladine, Beograd 1989.

[3] Prodanović, op. cit.

[4] Ј. Chevalier, A. Gheerbrant, Rijecnik simbola (Dictionary of Symbols), Nakladni zavod Matice Hrvatske, Zagreb 1983.

[5] This is confirmed by the individually conceived picture titles.

[6] П. Донков, „Морални избор пред лицем апсурда“, ( Moral Choice in the Face of Absurdity), exh. cat., (the Salon of Niš) Нишког салона 12/2, Галерија савремене ликовне уметности Ниш, 2022.

[7] L. Mamford, Priča o utopijama, prev. A. Golijanin, Gradac, (The Story of Utopias, transl. A. Golijanin), edicija Alef, Čačak 2009.