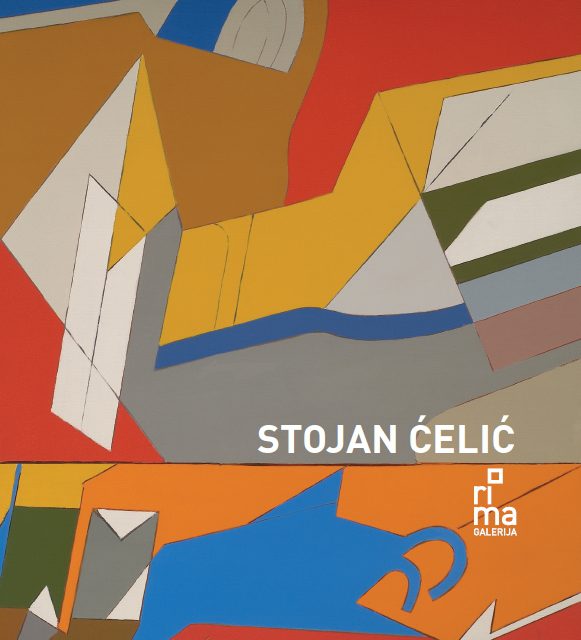

Lidija Merenik

THE MODERN PROJECT OF STOJAN ĆELIĆ

„Personal life, learning and history progress with hesitation and are not moving straight towards the goals or concepts. What one is looking for definitely, one never gets, but ideas and values are never in short supply, on the contrary, particularly to him who is able to free a spontaneous source from his meditative life.“[1]

When Stojan Ćelić returned to Belgrade in 1948, and to his studies[2] interrupted by the inexorable rhythm of war years, he continued the courses with Đurđe Teodorović, and later in the class of Nedeljko Gvozdenović, with whom he graduated in 1951. He used to say about those days, „with Čelebonović we learned the true splendour of painting, with Lubarda the limits of ascendancy, with Gvozdenović what one can get engrossed in in full maturity, with Tabaković how to reach spaces of the irrational…“[3] During his studies he found the lectures on early renaissance in Italy, held by Momčilo Stevanović, of particular importance, as if the expert oratorical skill of Stevanović helped Ćelić understand properly the history of painting and the establish the fundamental paragons of his future opus. On the other hand, in 1949 Ćelić went on his first visit of the mediaeval monasteries of Serbia and Macedonia. Owing to the time spent with Aleksandar Tomašević (about whom he would write one of the best and most inspired texts ever written about that artist[4]), and his participation in the exciting preparations (1948-1950) for the Exhibition of Yugoslav Mediaeval Art (1950, Paris), Serbian-Byzantine art became a model stimulus of Ćelić’s future learned modernist expression, his contribution to the mediaeval-modern phenomenon in the Serbian modernist painting where Aleksandar Tomašević and Lazar Vozarević also produced their best works. Almost at the same time, in 1950/1951, Ćelić had his first exhibition and wrote his first text on art. Despite the fact that Stojan Ćelić holds a renowned place in the memory of post-war Yugoslav and Serbian culture of modernism primarily as a painter of an exceptional innovative and creative talent, it would not be an exaggeration to state that his art reviews and studies on art[5] (published in Mladost, Lik, NIN, Revija, Književne novine, Umetnost, Delo, etc.) had equal significance for the Serbian cultural circles as his artworks, making him an inseparable protagonist of Serbian art criticism, together with artists/authors such as Miodrag B. Protić and Zoran Pavlović. History cannot overlook the participation of Stojan Ćelić in the emancipatory gathering of modernist artists – the December Group (1955-1960). The Group comprised a number of different artistic expressions and inclinations[6], and its unifying factor was in spheres above the linguistic level of a painting, first of all in the need to specify the contemporary conception of painting in the 1950s, in a climate of renewed struggles for artistic freedom after the pronounced directive of the political-programmatic activities of socialist realism. Although the group, as Protić has written, did not have a uniform aesthetic platform[7], the December Group and Stojan Ćelić as its member, were consistently looking for and applying different conceptual, compositional and modernizing innovations of the painting: from the need to make a significant step forward from the model of inter-war Serbian art and „modern traditionalism“, over the compositional and formal testing of Picasso’s synthetic cubism and post-cubism, to the making of an original model of new painting, where Ćelić’ achievements were of capital value. As he said: „there must have been a strong point of these ’individualists’. We could come closer to truth if we sought that point in our appraisal of the entire opus of every individual. […] The December [group] was an offspring of its time and the agreement of its members was the result of their wish to unite their similar interests and expressions“[8]. Ćelić’s achievement is an individual, personal act of responsibility before art and the freedom of artistic expression, of the creative need to have a progressive original language for a new, modern and different painting in the political and social climate of the 1950s, the painting that could project its accomplishments into the future of art: „I have created and followed my personal programme, trying to solve the tasks I posed for myself, and I posed them and solved them in a world which did not allow for stagnation and impassability. […] the generation I belong to has influenced essential changes in our contemporary art of the second half of the century“.[9]

Artworks

- More about the artist