Nevena Martinović

VLADIMIR VELIČKOVIĆ IN THE 1960s: A CRUCIAL DECADE

The 1960s represented the pivotal decade in the creative activity of Vladimir Veličković when the artist produced a corps of paintings and drawings whose value was recognised and acknowledged at the most important exhibitions of Belgrade and Yugoslav art, including the October Salon (Belgrade, 1963) and the Triennial of Fine Arts (Belgrade, 1964), as well as Yugoslav exhibitions at the Biennial in Sao Paulo (1963), San Marino (1965) and Paris (1965). The award for painting at the Paris Biennial brought him a grant for a sojourn in Paris – the result of this was his decision in 1966 to move to France, work and develop in the framework of primarily Parisian but also international art scene. Behind all the public recognitions, in the privacy of artist’s studio, the sixties were marked by pivotal changes inside Veličković’s paintings and his referential leap from the local context of neo-surrealism into the then contemporary international discourse of new figuration.

Veličković’s painting from the last years of the fifties and the first years of the 1960s, the period when he exhibited with the Mediala group (1959, 1960), was marked by the scenes of secrecy and nightmarish atmosphere of dark Cellars and Dungeons, by portraits suggesting internal worlds of madness and trauma, or representations of figures and landscapes culminating in his monumental Scarecrows. Until the second half of the 1960s, Veličković’s works were analysed in Belgrade within the discourse of a reformed surrealist model of painting. The early interpreters of Veličković’s works found sources for his iconography in a specific choice of historic paragons – from Dürer to Goya, from El Greco to “the blue” Picasso, as well as in his childhood memories of disturbing scenes from the Second World War. Classification of his painting as neo-surrealist lasted in local criticism even after 1963. However, it was then that the first significant changes in Veličković’s model of painting took place.

At international exhibitions Contemporary Alternatives 2 (Alternative attualia 2, author Enrico Crispolti) in L’Aquila and The Contested Present (Il presente contestato, organised by Franco Solmi and Max Clarac-Sérou) in Bologna in 1965, the artist was for the first time placed into the contemporary context of new figuration. At the same time, at the Paris Biennial, Veličković received the Award for painting and the chance to continue his career in the capital of France. In Paris, he was almost immediately recognised by the art scene as someone who belonged to contemporary figurative tendencies in French painting. That was confirmed by his solo show in 1967, in Gallery Dragon, whose director, Clarac-Sérou was one of the selectors for the exhibition of new figuration in Bologna. Veličković’s friendship and cooperation with Gérald Gassiot-Talabot, begun at the show in L’Aquila, became more profound after his arrival in Paris. Talabot first wrote the text for Veličković’s solo show in Belgrade in 1969 and later included the artist in his own selection for author exhibitions in Paris: Everyday Mythologies 2 (Mythologies Quotidiennes 2, 1977) and Tendencies in French Art 1968-1978 (Tendences de l’Art en France 1968-1978, 1979). In the monograph dedicated to Veličković’s drawings (Vladimir Veličković – Dessins 1957-1979, 1996) Alain Jouffroy classified him among the crucial protagonists of renewed objectness and figuration in European art: “it was not only that American Pop-art artists renewed the elements of creativity, it was the European artists such as Veličković, Erró, Klasen, Stāmpfli, Arroyo, Schlosser, Dufour and Monory, who have performed ‘the revolution of gaze’, more important than Pop-art and mostly without any help from galleries or critics”.

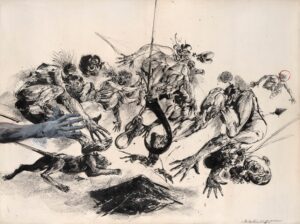

The classification of Veličković in international contexts threw new light on his works and the consequence of that were changes in the local theoretical analyses of his painting. The art magazine Umetnost (No. 9) published in 1967 a text by Ješa Denegri “Defining Elements of the Phenomenon of New Objectivity in Young Belgrade Painting” which gave important contribution to interpretations of the current situation at Belgrade art scene in the sixties. Within the heterogeneous phenomenon of new objectness Veličković’s works were categorised as the painting of “modern anthropocentrism”, delineating, “from Bacon to, for example, Maryan” such open and disturbing “graphic representations of fear” that surpass with their eruptions of horror all the devilish past painting”. Underlining the inadequacy of the term “surrealism” Denegri recognised as the departure point of Veličković’s works (in opposition to the suppressed traumatic content) the presence of “crude, cruel, superfluous, quick, primarily quick, momentary death in the spaces of contemporary urban settlements, on the flat surfaces of modern roads, at locations of the unfortunately still flaming warfronts.”

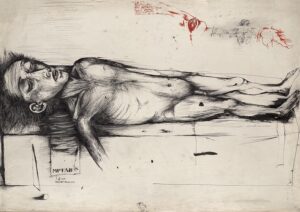

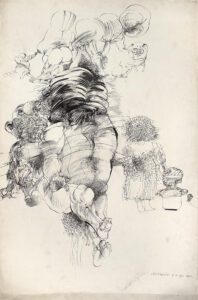

Based on Denegri’s conclusions about the contemporaneity of Veličković’s painting in the 1960s, the text in this catalogue brings condensed impressions about the three characteristics of Veličković’s paintings that placed the artist close to the European post-informel figuration. The first characteristic is his appropriation of documentary, newspaper photographs as iconographic and compositional departure points in his works and particularly his drawings and paintings from the series of Heads. Presenting them in totals of the widest exposition, the artist applied to the representations of distorted and crushed human heads the brutal ability of documentary photographs to confront the viewer directly, without warning or hesitation, with massacred bodies or heads distorted with pain, as simultaneous horrors of human crime and suffering. The second characteristic is his paroxysm of aggression and violence after 1963 – a state caused by the clash of two experiences, the one from the immediate and still insufficiently overcome past of the Second World War and the experience connected to the current situation of Cold War tensions, new global execution places such as Vietnam or Algiers, but also numerous places of disasters and crime, of which contemporary man is regularly informed by the media. The third characteristic refers to the procedure of piling up of forms as his artistic method of giving shape to figures and scenes in a picture. Such a procedure of building up a representation is close to the phenomenon of accumulation present in the works of many of Veličković’s contemporaries, including the famous representatives of new realism and narrative figuration, Arman and Erró. Veličković’s accumulation of organic shapes that underlines the violence and brutality of the scene is based on the situation when man is inundated and saturated by the scenes of violence in all the places of the globe. Anyway, the representations of corpses are only a few pages away from commercial advertisements and therefore crime is imposed as yet another element in the array of contemporary products. That product is in the centre of Veličković’s interest in the time and civilisation of his life and for it the artist finds the most adequate expression in accumulating horrific organic forms to the maximum saturation of the scene.

The selection of drawings at the fifth exhibition of Veličković’s works in Gallery RIMA is concentrated around a group of works produced between 1960 and 1971, as a reminder of this pivotal decade for the artist, primarily his representative works such as The Railway Man and The Drowned Man, analogous to his paintings of the same title; there is also his Composition produced in the Master Workshop of Krsto Hegedušić, his Bat, exhibited at the Biennial in Paris¸ as well as his Ripped Up Flower and Figure from the Biennial in Sao Paulo.