Nevena Martinović

Nevena Martinović

THE ART OF RADOVAN KRAGULY: THE REINVENTION OF MAN UNDER THE SIGN OF THE COW

(...)

In his works of the 1970s and 1980s Kraguly represented the character of the cold, merciless and amoral relationship to the animal in dystopic scenes of the dappled cow imprisoned in a small area of a field or within clearly designed constructions for the confinement and nourishment of animals surrounded by endless emptiness. By means of critical realism the artist carefully analysed and pictorially developed the space in which the cow lives. At first it is the space where, in comparison with the traditional rural household, man does not live with the animal – the space which has cancelled interaction – and the cow is observed from a distance. Primarily in the case of dairy cows it is painfully indicated that the machine has taken over milking, completely excluding the physically most important, and symbolically the deepest, contact between man and the cow. This direct absence of man during the process of using the animal severed the link between what the animal produced and the animal itself. The notion of milk is separated from that of the cow. Therefore, the space where it is required to spend its short life is created in accord with the human need for milk and not according to the needs of the cow. It is only a production machine in the complex producing section of the milk industry – at the end of its production capacity the cow would be reduced to the level of raw meat material.

Reason, as the highest signifier of man’s specialness in relation to the rest of the living world, has been presented here with its reverse side – as a generator of the pathological distance from the world man biologically belongs to, from nature and from the animal as its exponent closest to man. The strict Euclidean geometry that controls and dominates the organic forms in a painting represents the cleanest visual manifest of the Cartesian proposition I think, therefore I am. For that reason the space and construction created by man are presented at the level of an architectural concept, formally almost on the edge of abstraction and symbolically on the edge of metaphysics. They belong to the sublime world of ideas, unattainable by a simple cow, which is painted realistically as an ordinary physical body.

In certain works Kraguly eliminates even the scarce grass cover and places the cows on a constructed platform resembling a stage – a “man-made field”. This artificial incarnation intended for the human eye links the cow to zoo-garden animals. Apart from the fact that their lives would end in those man-made objects, they lead a life empty of identity where their nature is either undiveloped or diminished. Placed in an inadequate space with limited movement, without any contact with other species, or with their natural environment and food, all the animals are deprived of the stimuli which would cause them to manifest the characteristics of their own kind. While the total lack of interest and apathy in the animals from zoo-gardens seems to be an imperfection and inspires the development of more convincing settlements, in an industrial chain this is thought to be desirable and fostered towards more restrictions and making animals’ existence nonsensical.

Without any possibility to realise themselves as cows, these figures that stand immovable or lie lethargically are representations of their own absence. The final phase of man’s bestial masterplan had been realised – not only has the milk been separated from the cow, but cows as such no longer exist. Industrial conglomerates are thus no longer bothered by the need for moral justification - can one even talk about the monstrosity of exploitation and destruction if the animal does not show the characteristics of its nature? “In traditional cultivation animals were tamed and later killed, but there was still a symbolic relationship; in a laboratory setting with industrial breeding and extermination in the sloterhouses there is no longer any kind of relationship with them.” If zoo-gardens are “monuments to the marginalisation of animals” then modern farms are the markers of their total disappearance from human perception and experience of the world.

(...)

In the following years, particularly after his residential stay at the Foundation Bemis in Omaha, Nebraska (1988), Kraguly took a completely novel position with respect to the treatment of essentially the same subject matter. The germ of this new approach was a simple action by the artist on the occasion of his first solo exhibition in Paris in 1975. A group of young people paraded in the streets of the Saint-Germain-des-Prés quarter with aprons on their backs designed by Kraguly with printed traffic signs saying “Beware: livestock on the road”. Michel Gosme remembered that with this action Kraguly gave citizens a fresh impression of the animals they “hadn’t looked at so vividly in a long time”.

What was thus begun ripened in the performance the artist conceived with the choreographer Dalienne Majors during his stay at the Bemis Centre, which was premiered as a part of Kraguly’s large solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris in 1989. A group of dancers/performers, dressed in overalls with cowhide spots, “moved indolently, just like a herd of cows. The movements of the cattle were repeated; in a moment animals and people mixed together. It seemed that both were left at the mercy of the system that evaded them.” It was a form of identification, an attempt to enter the body of an animal by means of an art, a poetic invention “that does not try to find an idea in the animal, that is not about the animal, but is instead the record of an engagement with him.”

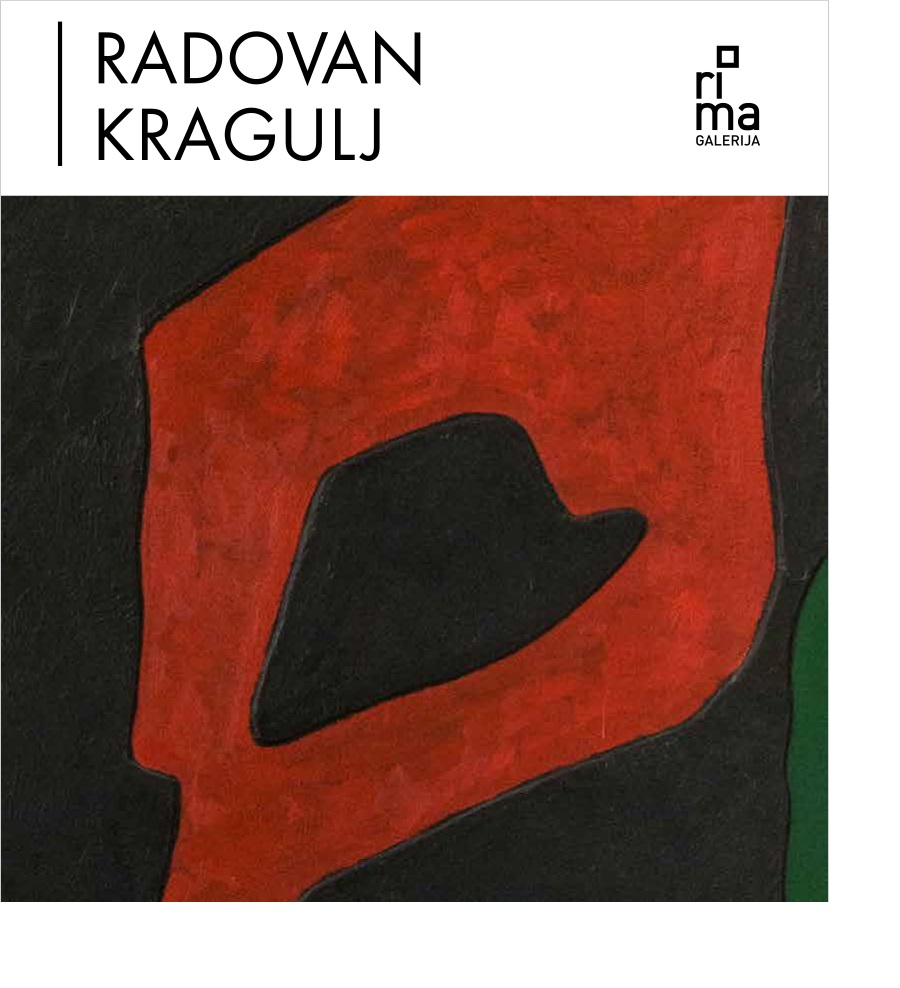

It was a matter of sharing corporeal reality in order to realise common existence. The same entering into the body of a cow occurs in Kraguly’s painting – the earlier scene of a herd first loses its morphological outlines in order to become a monumental field of black and white spots that cover the whiteness of earlier spaces by becoming the space itself. Kraguly pulls his paintings into the hide of the cow, he exchanges his fingerprint for the unchangeable form of a cow’s spot – he develops his own artistic identity under the sign of the cow.

Kraguly abandons forever the critical realism of the artist-observer and enters the period of identificational abstraction. The title Livestock is replaced by more abstract notions of internal motivations such as Impulsion (impulse, instigation, motive, instinct), Enchainement (connection, joint), Perpetual identification, and others. Concerning these works, interpreters of Kragulj’s art used to mention the fusion of the microscopic and macroscopic universality of the world, from cells to stars, all reduced to the representation of a cow’s spot: “(...) Each picture represented all the cows of this world and at the same time the tiny, imperceptible detail stolen from the back of a cow foetus (...). Perhaps we are confronted with a faraway form of non-transparent dust which sometimes darkens the Milky Way (...). Or are we looking at amoebae under the microscope, at the tiny parts of living cells?”

By connecting the physical identity of the cow with symbols of our common world, such as the Milky Way, Kragulj endeavours to revitalise its place in the collective memory of contemporary man and, contrary to its perverted image in pop culture as a derivative of the consumer society, to renew its archetypal qualities. What is more important in these works, however, the artist reveals the evolution of his own relationship to the animal, assuming the refusal of the strictly binary position between man and the animal, even the overcoming of the traditional dual relation towards the animal, which was part of his own upbringing. Living in a time of major ecological incidents when domestic animals were severely destroyed, Kraguly joined to his artistic practice the general position of the 20th and 21st centuries that refutes the anthropocentric assumptions of the world, from the movement for animal rights, through environmentalist philosophies, to scientific findings that confirm the closeness of man and the animal on all levels. In that sense, it is necessary to turn to those interpretations according to which the spots in Kraguly’s works are territorial and geographic and “delineate regions, spaces, provinces, borderlines” and therefore “remind one of outlined broken borderlines that surround us in the physical world.”

The space whose imaginary mapping is reconstructed by Kraguly in the cowhide spots is not a tangible territorial limens, but an ontological borderline belt between man and the animal, reflected in physical relations as well. The irregular forms Kraguly used to cancel the former geometric structure first refer to the two-centuries-old idea about the precisely drawn straight division between man and what constitutes the animal. In the changeable disposition of abstract spots, in their overlapping, stratification and multiplication, in their discontinuities and overspilling, in their permanent growth and spreading across the picture field and outside it, it is possible to recognise Derrida’s deconstructivist understanding of the borderline between the world of people and the world of animals. Derrida introduced the term limitrophy for his thesis on the specific experience of the borderline. The term is of French, or Latin, origin and derives from the adjective limitrophe/limitrophis meaning bordering, neighbouring. It is used, in particular, in relation to the provisions and upkeep of border areas. It is interesting that the meaning of the word tropos/trophē/trephō, particularly important for the understanding of the entire notion, Derrida described in a natural analogy “to transform by thinking, for example in curdling milk.” He insists on the heterogeneous multitude of the large but collectively observed animal realm, on the awareness of innumerable and diverse non-human beings with whom man shares different degrees of closeness and differences. Hence one homogeneous continuality does not exist, but rather a borderline composed of a multitude of “internally divided lines“ that make it fluid, incessantly growing and impossible to objectivise. In Kraguly’s works produced since the second half of the 1980s and the 1990s, in which he developed abstract fields of irregular spots, we recognise a quality very similar to Derrida’s experience of the borderline – the continual provision of new forms, their unlimited spreading, their uncatchable multiplication, their mutual “thickening” and entangling, all realised through the relationship of the spots, each of which is particular and unrepeatable.

The same experience of growth and multiplication is achieved in the forms of monumental polyptychs that Kraguly made initially in the late 1980s, but first of all in their media stratification which develops exponentially – from picture objects where he uses different materials (such as wood, paper, lead, graphite, etc.) and treats them in different ways, through assemblages with crumpled cloth and pieces of human clothing, to complex spatial installations with ready-made objects, sculptures, photographs and videos. The synthesis of different experiences created using various media, as well as different kinds of artistic expression, produces a saturation of diverse relations to the animal, destabilising or deconstructing our one-sided humanitarian position.

This pluralistic and multi-dimensional approach to the topic of man’s relation to the animal achieves its climax in Kraguly’s complex multimedia exhibition projects, which occupy not only galleries but also public spaces, then include performances and interventions in space, and involve audiences in various ways. Finally, by treating his painting and multimedia works with the subject of the cow as “work in progress” – work that constantly multiplies and becomes more complex, with no final conclusions or sharp artistic cuts, the artist adopted the experience of the borderline as the life-giving instrument of existence – of art, the cow and man.

(...)

On the occasion of the multimedia exhibition project Kraguly. Hathor: VLK, realised in Belgrade in 1998, in his short explanation of his artistic practice the artist stated: “The continual distancing and separation of man from his nature is the prime subject matter of my works”. In his entire opus Kraguly used to impress us with the realistic meticulousness of the figures of domestic animals and their environment, he hypnotised us with endless fields of cow spots, suggestively mixed our reality with the reality of his works in installations with real cages, fodder and farm objects, enthralled us with the choreography of cow-like dancers, left us absorbed in thought in front of the sign of cow’s horn and the complex symbolism of the goddess Hathor, inviting us on an imaginary walk through his Dairy Museum. Since as observers we are directed to the animal in Kragulj’s works and confronted with the tragedy of its existence in the highly industrialised world, it seems necessary to underline once again that man, who is responsible for the destiny of domestic animals in a developed consumer society, remains the “primary subject” of the artist’s thinking and creative activity – the one the artist addresses with each of his works. The relationship to the animal, as a paradigm of man’s understanding of himself and the world, has always anticipated the relationship to another man, to the one who is understood “as the other” for any reason. Therefore, it is not accidental that Kraguly, like many leading thinkers of his time, compared contemporary farms with concentration camps, and identified mass killing of animals (the destruction of livestock) because of epidemics with genocide. Kraguly’s overall artistic practice was, in fact, the artist’s inspired contribution to the struggle for a new humanism, for a radical change in man, individually and collectively.

/ complete text in the printed edition /