Sofija Ž. Milenković

Sofija Ž. Milenković

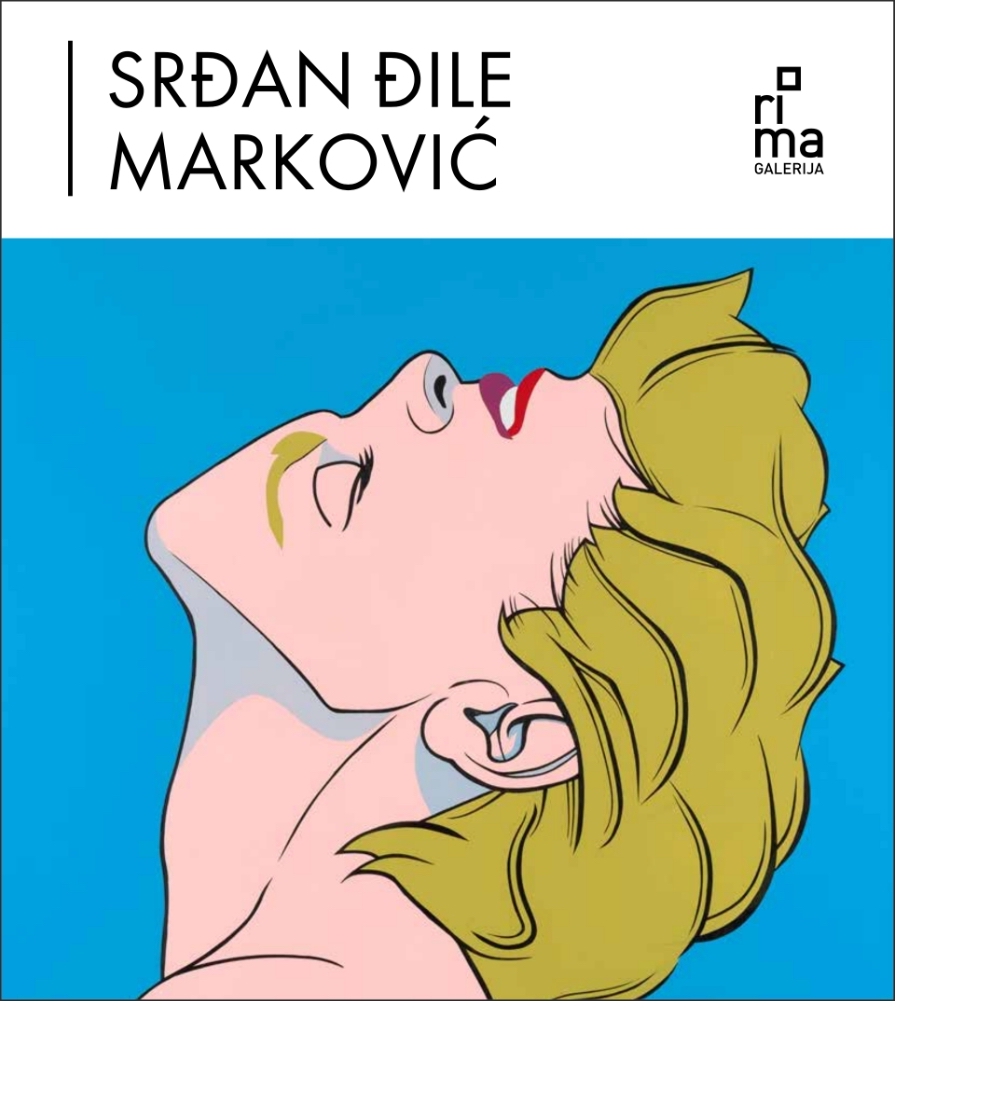

SRĐAN ĐILE MARKOVIĆ, The distorting mirror of social archetypes

The painting of Srđan Đile Marković, with its roots in the sub-cultural ambience of „Belgrade underground“, is contained in the fluid and multilayered concept of „underground“ art, most broadly involving every resistance to high art and the effects outside institutionalised artistic system by a deliberate assumption of alternative, or off position. Although he had worked on his identity of an intermedial artist in his formative years at the alternative club scene, gathered around the Students’ Cultural Centre and the Faculty of Fine Arts Club („Akademija“), as well as the entire new wave, characteristically his art – at least his painting – found its proper place within the context of high culture as well, where it appeared as an ideal representative of its sub-cultural milieu. In that way Marković’s painting entered the “interspace between high art and underground”, as proven by his cult picture Crowd (1991), today in the collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade. And finally, Marković has retained his position of an artist-outsider while his painting has remained “underground”, but only to the brinks of the particular sensibility he emanates.

There are many origins and strongholds of Marković’s figurative painting: from the German social are of the 1930s, the tradition of New objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), over American underground comix and particularly Californian underground (lowbrow) figuration of the 1980s and 1990s, to the painting of American artists, predecessors of Pop art, such as Philip Guston and Peter Saul. Common to these artistic phenomena, and thereby crucial in Marković’s painting, are their social thematic, commitment and reaction to the existing social and political circumstances, figurative painting and ironic or satirical representation of the reverse side of social reality. The artist is inclined to diverse eclectic and mimetic strategies, primarily symbolic in his works, just like the Op art “aureole” in the painting Investor, frequently playfully ambivalent, but not connected to the figures represented on the canvas. The strategy of Optical art is more frequently present in Marković’s recent paintings and is one of the examples of his flirting with styles in the already perceived playful and frequently mimetic manner which re-examines man’s perception and subsequent cognizance of the perceived. One can recognise in this the distorting intention of the artist, in fact the parody he applies in dealing with the rules of style unity and places himself at a distance from the habitual ways of artistic strategies.

With the exhibition in Gallery RIMA Marković is making two steps forward in relation to his previous three-decades long practice: certain works are purified and devoid of detail, and colours are darker. The artist points out that this change is due to the manner in which we see colours today when our eyes are in permanent contact with smart phones, computers and TV screens; on the other hand, their advertising aggressiveness is no longer new and surprising, but a part of our everyday life. Bright and fluorescent acrylics are no longer equally conspicuous as in the previous, technologically more modest context of creation. The darkening of colours is the result of Marković’s visible need for the rigid early vector illustration and the choice of Hard Edge painting that demands exceptional precision in delineation of lateral lines and their uniform saturation with black colours – obtainable only with a tranquil, technically precise and careful movement of the acrylic felt pen, The artist’s persistent adherence to the American comic strip tradition of the 1960s lies in that endeavour, accompanied by the magnifying practice of miniature stills of his early illustrations . However, Marković is singled from that tradition by the colours non-existent in the printed comics of that tradition. By a uniform layering of acrylic non-mimetic paint on the canvas, the artist endeavours to attain the impression of printed illustrations, or the “mechanical procedure of colour creation”, for the purpose of a perfectly caricatural representation of Hard Edge painting.

The artist’s departure point is not an interpretation of reality but the uncovering of social myths and social archetypes through grotesque representations of “notable” individuals from the existing society. In the time of post-truth, no longer novum, reality is exceedingly showing the characteristics of a silumacrum where one has difficulty in imagining the outlines of the real and Marković’s painting appears like a magnifying glass much more clearly indicating the scandalous forms of life we hardly notice and eventually completely lose from sight because of our overt obsession with reality. Figures are crowded in an almost iconographic perspective, seemingly known to us, but never a direct allusion to real personalities. Since these representations prompt associations to recognisable characters it could mean that the artist has found the “code” of the mental and aesthetic structure of an overtly transparent mentality, or the entire social principle.

The artist assumes we live in the time of crowds and therefore these should be represented with figures piled up to the very edges of the canvas. In such a way he creates an emphasised narrative character of his composition with time-honoured recognisable subject matter (spanning four decades), formulated within the context of the late 1980s and during the crises-burdened 1990s – sex, violence, drug taking and all other characteristics of the life on social margins. With the change of political and social context, by the enthronement of hyper-consumerism to the pedestal of supreme social values, Marković refers to the new “higher class” and its consumer habits (Investor, Laser Action) which he finally and ornately makes meaningless with his satirical representations. His big format canvas entitled Golden Years places in its centre a figure that enlightens all the nonsense of the metaphor about golden years, or man’s happiest age – the golden age leaves only golden cockroaches on the canvas, as symbols of neglect and a feeling of unpleasantness, while the dark gaze hardly visible under the whirling, hypnotic grey hair conveys the message how difficult and ugly it is to get old and how quiet old age is only a story never truly experienced by anyone.

With the many quotations the artist paints thematically uncoordinated and unlikely figures, interweaving comic strip heroes with characters from urban mythology, so that one canvas can simultaneously show figures as reflections of the local social realm and also references to the heroes from Marvel and DC Comic strips (The Weight of The World, Vernissage) without a defined and interrelated symbolic function within the same plane. The artist frequently refers to his own figures of personal mythology, such as the Floral-eyed creature from the flower- pot or the already cult “heroes” of his Crowd. In such a way artist re-examines the concept of originality in art and in his specific parodic manner underlines that such gestures can only be responses to the requirements of the local market requesting a re-interpretation of “famous” figures. Thus they create a galimatias that does not condition the observers’ narrative course, but allows each of them to make individual associations and reactions; all the while one has a feeling that the artist has an ambivalent position. “Man follows his convictions, regardless of their true meanings”, repeats Marković offering the observer a chance to see even those individuals and social strata whose existence we often want to annihilate, but he does not oppose our conscious choice not to see and thus defend our independent truths. For that particular reason his art is not moralising, but an intimate and independent criticism, leaving observers the freedom to recognise social archetypes emerging even uglier with every new crisis, but easily spotted in the “crowds”. For the past four decades, Marković’s big-format canvases contain a transposition of social hypocrisy and overall nihilism – thus “the time of crowds” can be unavoidably understood both as the time of crisis and the time of incessant production of meaninglessness to which one should not get accustomed but should steadily and constantly unmask it “in the small, small, very small country with little time to waste”.