Nevena Martinović

Nevena Martinović

ĐORĐE IVAČKOVIĆ AND THE PARIS BIENNIAL OF 1965

When Đorđe Ivačković settled permanently in Paris in 1962, he was thirty-two years old and in the milieu he had just left, in Belgrade, he was known as a jazz musician with a B.A. in Architecture. Nevertheless, his passion for painting and his painterly practice, then completely unknown to the Belgrade public, were the real reasons for his going to the City of Light. He wanted to devote completely to painting as his life’s career in the social and cultural-artistic milieu of Paris and present his works there for the first time. „Paris is the concentration and fermentation of intellectual activity of a heterogeneous mass of artists from the entire world. I wanted to be accepted in the situation of numerous influences, in that fusion, to have the characteristic quality I brought along and the way in which I expressed it to be appreciated, I wanted my work to acquire the quality of a common denominator of the global mixture, briefly, a universal meaning. That is the sense of my work and sojourn there“ , explained Ivačković in one of his interviews. The acceptance and recognition within the Paris artistic scene evolved slowly in the first years and assumed a gradual representation in group exhibitions, as well as his first solo show in 1963. However, the event from the early years in Paris which had a crucial role in the affirmation of Ivačković’s painting was his participation in the Paris Biennial in 1965.

(...)

Đorđe Ivačković was in the group of chosen painters thanks to Jean-Jacques Levêque who he had met a year earlier and who was able to draw the attention of his colleagues to the young painter of Yugoslav origin. Ivačković and Levêque were not only related by their love for painting, but also for their weakness for jazz music and the beginning of their professional cooperation was Ivačković’s first solo show organised in the Paris gallery Le soleil dans la tête in 1963. In a short text dedicated to Ivačković’s painting, published in a modest brochure for the exhibition, Levêque compared Ivačković’s short strokes with those of Thelonious Monk on the piano. Along the same interpretative line – of abstract painting inspired by jazz music – went the majority of subsequent reviews of Ivačković’s painting in the 1960s. Ivačković himself contributed to this approach by getting close to a group of visual artists inspired by jazz, whose custodian was mostly Levêque . For that reason, undoubtedly young critics got acquainted with Ivačković upon Levêque’s recommendation and the outcome was a unison invitation to participate in the Biennial.

His participation at the Biennial in Paris in 1965, and within the French selection, had a decisive influence on Ivačković’s position on the art scene in Paris, but also on recognition and presence of his artworks internationally. The first encounter between the public and the Biennale happened in the large hall where the visitors began their tour of the museum. Because of that such a position was a particular advantage, especially for less known artists who were able to get better known by all the important members of the cultural and artistic scene of Paris and international audiences during the four weeks of the Biennial (28 September – 3 November, 1965). Apart from that, two additional exhibitions were organised as accompanying programme and again in the selection of young critics. One show was held in the Gallery Le soleil dans la tête and in the case of Ivačković one was invited to study those completed paintings produced at the same time as those exhibited in the museum hall. At the other exhibition, in the Gallery Peintres du monde, artists mounted works of smaller format, but still important for their overall opus.

Ivačković’s participation at the Biennial had two immediate results. The first referred to his strengthened exhibition presence in the art circles of Paris in the second half of the 1960s. Excluding his participation at exhibitions dedicated to the link between contemporary art and jazz, a specific place belongs to his participation in the group show The Spring in Paris that opened the Gallery Cimaise Bonaparte (the future Gallery Templon) in 1966. On this occasion Ivačković gave his first interview, published in the modest exhibition catalogue. His cooperation with gallery owners Patrick d’Elme and Daniel Templon brought about the second solo show in the same space a year later. The other significant result of Ivačković’s participation in the Biennial was the fact that Yugoslav public could get acquainted with his works. Namely, before he had permanently moved to Paris in 1962, he had no public showing of his works and not many people knew about his painting although his artistic activity had begun in Belgrade. Therefore, the encounter with his large format paintings at the Biennial, and within the French selection, was a real surprise and revelation for members of the Yugoslav delegation. Shortly after that he was invited to participate in the First Triennial of Visual Arts in Belgrade and it was, at the same time, Ivačković’s first exhibition in Yugoslavia. It was the beginning of the many decades long presence of his abstract painting within the framework of Serbian and Yugoslav contemporary art.

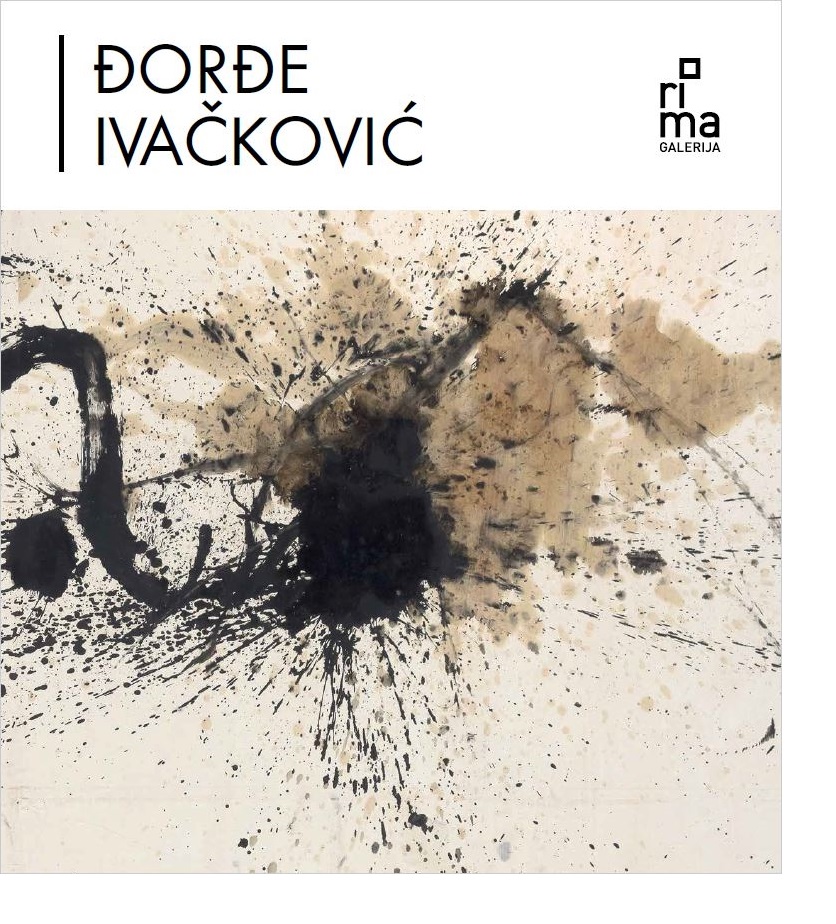

While his participation at the Paris Biennial was the crucial instigator of progress in Ivačković’s career, preparations for that show were particularly important for his painterly practice. In the summer before the Biennial, in a rented, run-down but spacious hut, he painted a small series of paintings c. 260x240 cm and three of those works were chosen for the Biennial. Because sources are scant and there is no precise information in the available sources , it is difficult today to establish which of the works were mounted in the museum hall. However, photographs of the frail temporary studio from 1965, preserved in the artist’s personal archive, confirm the presence of a group of paintings in those dimensions, but also of other pictures painted at the same time. One can recognise in those black/white photographs completed and incomplete works including two paintings presented in the RIMA Gallery for his exhibition there. Since Ivačković never returned to painting on paper in these big dimensions ,we can ascertain that those works seen in the photographs were made for the occasion of his participation at the Biennial, including four pictures found in Ivačković’s family legacy in Paris and presented in the Belgrade gallery more than fifty years later. And finally, on the basis of the signed dates in those paintings we can conclude that all four of those works were produced in August 1965 - in the summer when all of the chosen artists were preparing works for the Biennial. Therefore, the works presented in Paris in 1965 and those exhibited in Belgrade in 2020 belong to the same group of paintings, produced for the Biennial in the summer of 1965, and show the characteristics of the same poetics and the same creative procedure.

In line with the modest circumstances in which he lived and worked in Paris in early 1960s, Ivačković mostly painted on papers of small to middle formats. The commission he received regarding the Biennial exhibition was his first challenge to paint in formats larger than human dimensions, and it had significant influence on his painterly procedure. The realisation of this challenge did not change Ivačković’s approach to the picture essentially based on the harmony between two different values – the trace of colour as a visual art element and the artist’s gesture, i.e. the painting as an autonomous reality with its own rules and the painting as the space of artist’s expression. Within such a nature of the picture Ivačković found very early an emphasised expressive creative procedure: a painting is produced in an unforeseen moment of inspiration and in a quick procedure, intensive and short, after which the picture is completed without the possibility of subsequent interventions and changes. Nevertheless, working in large formats brought about a hyperbolic or exaggerated physical relationship to the picture. In order to conquer the surface of the painting much larger than his own height and reach, Ivačković used to place large pieces of paper on the floor of his studio (as proven by some photographs) and painted moving around and across them. The foundation that earlier used to represent the significance of the background and a visual art element, took over also the role of the space in which the artist moved and effectuated his painterly activity. The painterly process now required artist’s complete bodily engagement because only with movement Ivačković was able to reach all the parts of the foundation; in consequence, this process brought him closer to action painting. This is confirmed by those parts of his paintings where paint could freely sprinkle after the brush had hit the foundation or in traces left by semi-controlled dripping of the pigment from the tip of the brush. Sporadic imprints of the soles of his shoes or his palms make the painting an evidence and document of the artist’s dynamic physical presence as a result of his action in space. His relationship to music, primarily jazz, he used to listen to while painting, additionally inspired the establishment of similarity between the rhythm he felt and demonstrated with his entire body and the one he established in the picture by means of the basic visual art elements. Therefore, the specific climax in the positioning of painterly action in Ivačković’s work was represented by his subsequent partaking in certain performances of Phil Woods’ jazz quartet in 1968. While the musicians were playing Ivačković created his pictures in real time under the influence of jazz rhythms and improvisations. The attention of the public was thus concentrated primarily on the artist’s movement and behaviour – on his action where he was the main performer. The painting finalised together with the composition or the concert would appear to be the result of a single event, the consequence of action.

After the Biennial, large formats became Ivačković’s regular practice, and this confirms that the creative episode in the summer of 1965 had permanent influence on the artist’s practice. Papers and canvases of large dimensions, although comprising the same creative principles as smaller format pictures, became places of concentration of a much stronger physical action which was allotted greater freedom of expression with the introduction of spatial dimension. Therefore, as such, large format paintings always refer more directly to the presence of the artist and the trace of paint as an imprint of his existence and work. Just as he recorded on 14 May 1965 in his diary, preserved in the artist’s legacy: “Physical presence in the process of realisation – an evidence of existence”.

However, despite all of the above, the procedure of picture production, even when it acquired the characteristics of painterly action, was never primary to the painting. Not for one moment was a painting realised as a mere result or document of artist’s self-expression in painterly means, but on the contrary – in situations of emphasised physical engagement that process always respected the rules of the painting. From the very beginning Ivačković understood a painting as an autonomous reality whose nature was based on spatial (as compared to temporal in music) communication with the observer, so that from the series of elements the creator was forced to use, regardless of the type of picture, he was always establishing exclusively compositional relations between the line, the colour and the surface of the flat, two-dimensional foundation. Between 1962 and 1971 Ivačković made the most detailed and voluminous recordings in his journal where he used to express and study, in text and sketches, the different relations of visual art elements on the surface (lines, surfaces, light, colour), different types of composition, potentially different formats and ways in which he communicated with the observer, and numerous other issues related to the nature of a picture. In the year when he made paintings for the Biennial his recordings disclosed problems related to “the action of realisation” and its transposition into a painterly composition. Ivačković wrote then about “the degree of concentrated tension” and “the quantity and size of tension” where tension is identified with the concentration of artist’s activity in the traces on canvas. Then he analysed in a series of sketches “the flux of action” and concluded, among other things, that the first stroke established a relationship with the format of the foundation, while each subsequent stroke established the relationship with previous strokes and the format of foundation. Several notes written in August 1965 refer to the “concentration of visual art elements” in small and large formats and also the “uniform and nonuniform” of visual art elements. Ivačković’s analyses imply his concern over the painting as an independent system where the artist endeavoured to belong and within which he searched for his own identity. Those seemingly casual splashes produced in his creative play are never scattered over the whiteness of the paper at random and without control. On the contrary, if we consulted his small sketches in the journal, we would easily understand that their coordinates and interrelations had been analysed, tested and verified as carriers of certain kinds of composition with definitive communication potential. Ivačković called his creative procedure “pre-programmed automatism” because the choice of visual art relations in the pictures he was producing in the course of a quick and impulsive procedure (seemingly automatic) had already been deposited in his subconscious owing to the preceding analyses, sketches and pictures when he studied and appropriated them. The artist said about that: “There are no coincidences. Each action is a resolution, a conscious decision which receives its material expression on the canvas. My problem is to endow each spiritual state, each idea, with the suitable expression. The entire procedure implies that in the palette of infinite possibilities I find the corresponding relations, in order to achieve full identification of the idea present within me at that moment with all its material expression and image.” If we returned to his wretched studio from 1965, one of the photographs would confirm such approach: three smaller format paintings, mounted on walls, with a similar compositional arrangement. Dominant spots on each paper are positioned in the same parts of the pictures, as if the artist was at one moment fixed on a certain organisation of elements in the picture, on compositional relations he was testing and studying as visual expressions of the same internal state.

Towards the very top of one of the pages of the artist’s journal, under the date 25 August 1965, Ivačković wrote the following: “An artwork: a combination of concept and passion. Find expression for it.” And the combination of the expressive and analytical, of impulsive and constructive was what made Ivačković’s authentic synthesis in painting. Within this specific nature of his pictures, the balance between the network structure of those polarities moved in favour of one or another but their connection would never break. In the sixties and early seventies expression was a more dominant element in Ivačković’s communication with the observer, while the pre-programmed structure of the painting was recognised as a factor of diversification with regard to other expressive tendencies in abstract painting of the past and present. This was supported in Ivačković’s painterly practice not only by jazz music, but also by his work in large formats instigated primarily by his experience during the preparations for and participation at the Biennial in Paris in 1965.